An Edwards Mansion Imparts Visions of a Castle in the Sky

It’s the end of yet another glorious autumn day in the Vail Valley as Dick Rothkopf unfolds from a yoga pose on a “dharma wheel” beside his swimming pool, a sparkling sapphire jewel set in the crown of a breathtaking promontory five miles and a world away from Edwards Town Center. Just west of this watery oasis sprawls his 16,000-square-foot, eight-bedroom, 13-bath Italianate villa. The property includes a tennis court, an infinity hot tub, a greenhouse, an observation tower, a sauna, a gym, an indoor basketball court, a screening room rivaling CinéBistro, a caretaker’s cottage, a four-stall barn, and an artificial creek that waterfalls down the hill more dependably than the natural one sluicing the drainage below. Beyond that extends Rothkopf’s playground: 220 acres of backcountry, almost a whole mountain, laced with trails all to himself. And the valley’s 360-degree views? He has them all: of the Gore Range, Game Creek Bowl, the Lake Creek valleys, New York Mountain, the Mount of the Holy Cross, and Finnegan’s Peak, which he loves to climb.

Rothkopf stands, looks, and sighs. “A kid from Cleveland owns this,” he says.

He calls it Il Podere, an Italian word for family homestead. Like a boy regarding a masterwork beside empty bins once overflowing with Lego bricks, Rothkopf regards Il Podere with wistful pride; a grand project that unfolded over a lifetime now stands complete, rendered exactly as he imagined it, from the centuries-old Italian masonry of the chimneys to the secret passages in the dungeon. “It’s one big toy,” he says, drifting six, almost seven decades back in time.

Rothkopf recalls that his father, a no-nonsense Ohio dentist who worked the same steady job in the same staid office for his whole career, never put much stock in play. He saw little value in the toys his son treasured as a child: the wooden blocks, the electric trains, and especially the model rockets. (In fifth grade, Rothkopf chuckles, he nearly blew the roof off his school with one errant, balsa-finned cardboard missile.)

Instead of following a well-worn career path like the family patriarch, Rothkopf majored in engineering at Cornell in the late 1960s, studied for an advanced degree in international finance at MIT, and then moved to Europe, where he traversed the continent as a hotshot young executive, flitting from one corporate job to the next. In his twenties and thirties, he says, he managed his career like a “tumbleweed,” going wherever the winds took him, until he found fertile soil for his passions and then put down roots. “That’s how I started all my businesses,” Rothkopf says. “That’s how I met Annie.”

Annie, his wife, has eyes that bubble like mountain pools. She’s English; they met at a party in London in 1973. He was a Mobil Oil man. She thought he was, in British lingo, a “bounder.” But Rothkopf was determined. “I tumbled on to her,” he winks.

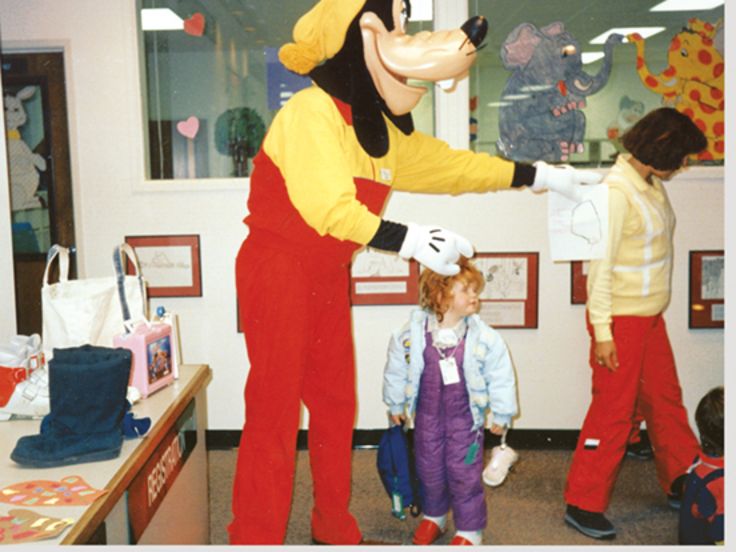

After they married, the couple bounded together through dozens of countries, a half dozen careers, five houses, and three kids. They did well for themselves. Then one day in 1992 in Portofino, Rothkopf says, he tumbled into a conversation with an entrepreneur who wanted to produce a line of wooden trains and tracks based on Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends, a TV series binge-watched by preschoolers the world over. The tumbleweed in Rothkopf again sensed fertile soil, and they became business partners.

After landing a license, with Rothkopf’s international business acumen, together they figured out a way to outsource the manufacturing to China at a fraction of the traditional cost. Then they cofounded Learning Curve International, a global educational toy company. As executive chairman, his life, once again, revolved around toys. Producing the Thomas & Friends Wooden Railway led to the manufacturing of similar Bob the Builder toys, then to a line of infant toys called Lamaze, then to another company, Ludorum, which created Chuggington, a train-themed educational TV show that was translated into 27 languages and broadcast to preschoolers in 127 countries across the globe. The success of all of these playthings begat the ultimate toy: Il Podere.

The estate, appropriately, derived its inspiration from family and fun. In 1993, the Rothkopfs purchased one of the first houses in Cordillera, just outside Edwards, as a second home. There was a hill nearby crisscrossed with informal trails, where the family loved to hike. One day, a For Sale sign appeared on 220 acres of the hill, offered by a developer who had planned to build 22 homes there but couldn’t figure out a way to access the steep and remote site. Having hiked there hundreds of times (and following the credo of Bob the Builder: “Can we fix it? Yes we can!”), Rothkopf purchased the property at a bargain in 2001 and spent roughly a million dollars and two years excavating a serpentine driveway that climbs 700 feet over a mile and a half. Then, it was time to build his dream.

Generally, when Joe Abbott is hired as a general contractor, he spends the first few weeks scanning plans, marshaling materials, and filling out forms. But when Dick and Annie Rothkopf hired Abbott, they approached things differently: they flew him to Italy.

For two weeks, through Umbria and Tuscany, from hill towns to seaside cities and from Florence to Positano, Abbott trailed the couple, seeking inspiration. “Dick knew exactly where he wanted to go,” Abbott recalls. His wife delighted in the architecture. Driving down a winding Tuscan road, for instance, Annie would spy a ramshackle homestead, jam the car into park, and implore Abbott to “Go take a picture of that!” Years later, some small detail from one of those photos—say, a carved-out shelf in a stone wall perfect for a small potted plant—would reappear inside Il Podere, as if by teleportation.

On that trip, the group also scoured the hills for the raw materials they would use to erect their masterpiece—the stone equivalent of the wooden blocks Dick cherished as a child. For this, they enlisted Annie’s friend of 40 years, Penelope Radford, who lives in Italy and has restored several buildings there. She steered the Rothkopfs toward reclamation yards, toy boxes stocked with intricately carved fireplaces, pale terracotta, hand-hewn limestone, and marble salvaged from manses and estates, some centuries old. “I still think the stuff here is better than what you can get in the States,” Radford says. “These materials have had another life somewhere else. There’s an innate spirit. You feel the age of things. There’s a softness.” The traveling party filled at least five intermodal containers with precious things, shipped them across the Atlantic, and trucked it all to Squaw Creek.

So, yes, Il Podere looks and feels authentically Italian. The living room is dominated by a centuries-old Tuscan fireplace and a long table from Cortona where monks once dined, Dick says, and the stone on the floor is from Padua. The cabinet in the family dining area is from Arezzo.

Yet despite its refined Italian pedigree, the home feels more playhouse than palace. Abutting the grand main wing, which has the “A” views and the master and guest bedrooms, a separate guest wing accommodates a second two-story living room (with a large flat-screen television hidden behind a retractable oil painting), another full kitchen, five more bedrooms and bathrooms (for their children) and a bunk room that sleeps six grandchildren or as many friends. Each kid helped design their room; when one daughter asked for a skylight, Dick and Annie gave her a lighted domed ceiling painted with the Milky Way.

Some toys—including a yellow Bombardier ATV, a couple of Polaris snowmobiles, two Honda dirt bikes, and lots of sleds—are played with outside. But Dick’s favorite toys are kept in the lower level, a subterranean lair meant to evoke a medieval castle dungeon. The narrow passageways lead not to cells or torture chambers but to an indoor basketball court and an elegant home theater (modeled after the Cinema Rialto in Rome) with electric reclining seats, where Dick screens new episodes of Chuggington. Another hall leads to a wine cellar where bottles are stacked floor to ceiling, then to a wood-lined sauna, a steam shower, and a locker room for guests, and further to a gym with cardio machines, free weights, and a massage and yoga studio that opens to the outdoor hot tub with its infinity edge and views of every mountain range in the valley. Climate, lighting, and music are controlled by an iPad app or touch screens on the walls.

Even some walls are toys. The rack that holds the cues for the pool table in the dungeon’s billiard parlor is more than just a rack: if you jiggle a certain cue in a certain manner, the seemingly solid wall swings inward to reveal a secret room that Dick calls his “Bad Boy’s Room.” It’s furnished with a poker table and a fridge stocked with beer.

On another dungeon wall that doesn’t rotate hangs a work of art consisting of a bunch of wooden blocks with an old-fashioned store sign that announces simply: “Toys.”

Annie’s toys are in the kitchen. Her wood-fired pizza oven, no Easy-Bake, would elicit envy from fourth-generation pizzaiolos from Naples. One autumn night, she serves her guests homemade pizza with fresh mozzarella, leeks, garlic, chives, scallions, and ... and ... “I forgot the bacon!” she gasps, slapping her face with a hand coated in powder, leaving one cheek a quarter geisha. She laughs and wipes it off.

The next morning, Dick bounds around the property, ever the tumbleweed.

One last thing about tumbleweed: When the plant senses that it’s been in one place too long, it detaches itself from its roots and rolls away. Dick, young at heart (he’s currently chairman of the board of Sky Zone, a company that builds indoor trampoline parks) yet undeniably older, put Il Podere on the market (it sold in March, 2019, for $15.4 million) and plans to downsize to a new and smaller home in Sonoma, California.

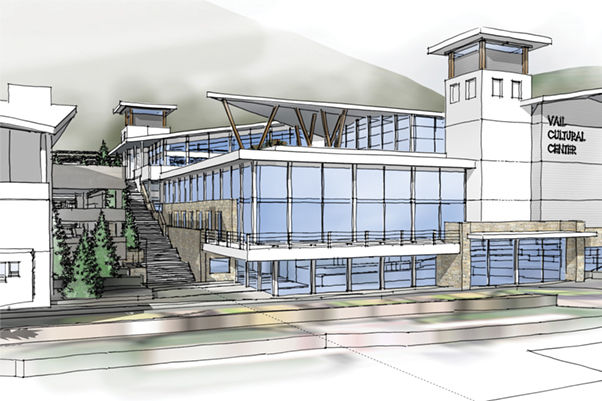

Today, he cuts his customary walkabout short because he has an appointment in Omaha, where he’ll meet with Warren Buffett’s daughter, Susan, who administers the Buffett Early Childhood Fund. Rothkopf would like the fund to help pay for a new preschool that he (and the school district, county, and influential friends) are working to build in Edwards. “People think you can just put kids in the closet for the first three years and then bring ’em out,” he says. “But that’s when the neurons are developing.” If it gets built, you can bet Rothkopf’s school will have two things: toy trains and wooden blocks, the stuff of childhood dreams.