Reaching Out

Dr. Jeffrey Resnick in his office in Edwards

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

The Colorado High Country is blessed with some of the most giving individuals in the nation, philanthropists who freely donate their time, money, and considerable professional expertise. On the receiving end are countless nonprofit foundations, groups, and organizations focused on everything from early childhood development to eradicating diseases to building affordable housing.

The region also benefits from the efforts of some of the highest-quality medical practitioners in the nation, if not the world. Some of the best surgeons in virtually every specialty work here in private practice, at the nonprofit Vail Valley Medical Center, or at the world-renowned Steadman Clinic and Vail-Summit Orthopaedics.

Auspiciously, a tremendous degree of overlap exists between philanthropists and medical professionals. High Country doctors and other medical personnel frequently travel around the globe to perform procedures and donate care often unavailable in developing countries, volunteering their time and energy to improve the quality of life of thousands of children and adults throughout the world. Here are some of their stories.

A Story of Healing

Jeffrey Resnick hails from L.A. (Brentwood, no less), is a plastic surgeon, and even had a star turn in an Oscar-winning movie. But that’s where all of the stereotypes about his professional specialty break down.

It takes less than 10 minutes of talking to the plainspoken, affable 56-year-old, a reconstructive and cosmetic plastic surgeon at the Vail Valley Medical Center since 2008, to realize that he has a deeper medical mission at heart. It takes a little longer than that, and even a bit of prying, to get him to talk about A Story of Healing, which won an Academy Award for best documentary short subject in 1997 by following three plastic surgeons—including Resnick—doing volunteer reconstructive surgery in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta on 110 children with various birth defects and injuries. The film stemmed from Resnick’s long-standing work with Interplast (now ReSurge International), the oldest among several nonprofit, charitable groups that send volunteer surgeons around the globe to do reconstructive surgery on burn victims, cancer victims, and children suffering from various deformities, including cleft lips and palates.

Resnick’s philanthropic work started during a fellowship in Southern California in the late 1980s, when he started taking an intern down to small Mexican towns and performing surgery on children in Red Cross clinics. The work took full flight during his residency and surgical training at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital, where he joined an informal group that took volunteer surgical trips to Vietnam. That experience led to a connection with Interplast, which was interested in doing more in Southeast Asia.

Since then, Resnick has spent at least two weeks a year in places such as Vietnam, Nepal, and Myanmar (Burma), restoring capabilities to developing children whose deformities otherwise would have constrained their lives from an early age. But even his day job in Vail involves a fair amount of reconstructive surgery, as opposed to the elective cosmetic surgery that has prompted a wave of reality TV shows in recent years.

“Plastic surgery is related to plastikos, which is a Greek term meaning ‘to restore,’ and plastic surgery is always something that’s been involved with reconstruction,” Resnick explains. “Most people think of it as cosmetic surgery—and that’s a part of plastic surgery—but reconstruction is a really large part. Even here, I do breast reconstruction, I do facial fracture reconstruction, I do any type of tumor surgery or reconstruction.” In fact, Resnick was recruited to the Vail Valley Medical Center because of the Shaw Regional Cancer Center, which had a need for his reconstructive expertise for patients recovering from a variety of cancer surgeries.

New empty-nesters—they have one son who’s a musician in New York and another who’s a senior at the University of California at Berkeley—Resnick and his wife, Michele, were glad to make the leap from the demographically similar but climatologically divergent city of Brentwood to the Vail Valley.

“I love it here; I kind of settled in after about 30 minutes,” Resnick says. “My wife kind of misses L.A., but she’s coming along. It’s a very, very welcoming community, and everyone has made us feel very comfortable right from the beginning. I think my wife has more friends here now than she ever did in L.A.”

And it’s not as if Resnick is unaccustomed to mountainous regions. He still recalls fondly his forays into Nepal in the early 1990s. There, Interplast started working with a young doctor named Shankar Rai, who was raised in that nation’s hill country and had had limited surgical training in Kathmandu. As he gained more experience with each successive Interplast visit and later underwent more surgical training in the United States, Rai became skilled enough that he eventually eliminated the need for the visits.

“Now no one goes to Nepal, because he has his own fellows and travels doing cleft lips and palates, and he set up a burn unit in Kathmandu and does all the major burn cases in the country. Pretty impressive,” Resnick notes, adding that teaching has become an increasingly important part of his overseas trips. But there typically are huge odds against local surgeons having the same success, particularly in war-torn countries.

“That’s always the goal, but it takes a very committed individual. And he is a very committed individual, but he was doing it against pretty awful odds—the whole Maoist revolution. He would go out in the country with his fellows and take bribe money with him because he’d be stopped all the time, and unless he paid them off, they would kidnap him.”

Not something plastic surgeons typically have to worry about. In L.A. or in Vail.

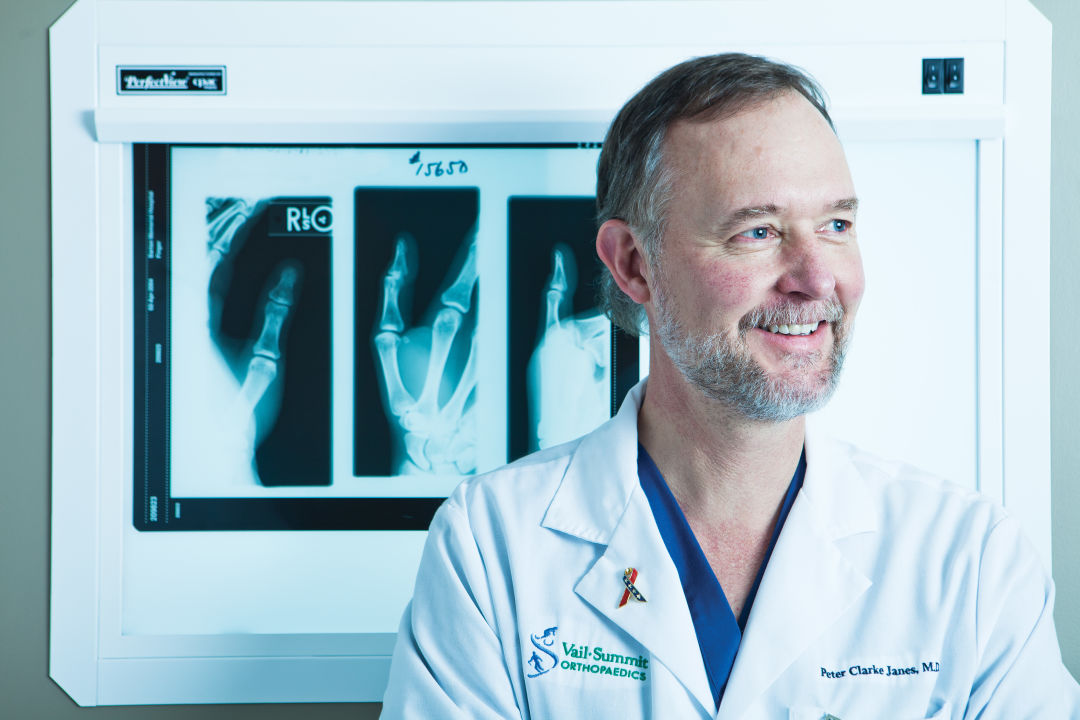

Dr. Pete Jane's practice takes him far beyond Vail-Summit.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Two Specks of Sand

In 2005, Peter and Patti Janes traveled to rural Uganda with their three kids, then aged 15 to 21, to hack trenches into the ground and bring water closer to the local village. They did so at the request of a friend of theirs in Denver, a Ugandan minister—it was his village, and his people needed help.

The Janeses toured three hospitals in Fort Portal, and Peter, an orthopedic surgeon with Vail-Summit Orthopaedics, couldn’t help but notice the vast medical needs of area residents, including a tiny boy with a clubfoot. Normally the boy would have been doomed in the rural area, but Peter knew to put a cast on his foot, improving his chances for a rewarding life. From then on, he asserts, “I decided my experience and training would be better used in a surgical setting than getting blisters on my hands digging ditches.”

Patti Janes, a registered surgical scrub nurse at St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in Frisco, has teamed with her husband on a number of missions since then, but those collaborations are only a fraction of the trips she’s taken. She’s been to Africa five times and Honduras 19; on her latest Honduras trip, she was the most qualified medic on a team that treated people in 18 villages and taught indigenous residents how to administer first aid. The final mission she took last fall was her sixth of the year, including three to Honduras, two to Rwanda, and one to earthquake-ravaged Haiti. (Peter joined her for one of the Rwanda trips and the mission to Haiti.)

“The trips are both rewarding and frustrating, because you can’t help everybody,” Patti explains. In Rwanda, they treated a month-old femur fracture and a boy whose radius bone had been sticking out of his skin for a year. They also spoke with a hospital worker who lives among the same people who murdered his wife and children during the genocide, when 10,000 people a day were killed for three months straight.

“They tell me, and I find it hard to believe, that they have two orthopedic surgeons for 10 million people in Rwanda,” Peter says. “We have 20 for two counties.”

On another trip, in 2007, the Janeses flew to Tanzania to volunteer at a 400-bed Norwegian hospital in the middle of nowhere. While they were there, a rabid hyena attacked four villagers. An old goatherd had his eye ripped out, a testicle bitten off, and lost both thumbs and three other fingers while trying to protect his animals. A 12-year-old girl was walking to school when the hyena bit through her skull and ripped off the left side of her face. Both survived.

“Those kinds of things stick with you,” Peter says. When asked what she takes from such experiences, Patti replies, “That I’m a tiny little speck of sand touching another speck of sand and making that one person’s life better for one day.”

The Janeses, who spent nine years in Eagle County before moving to Breckenridge in 1995, have been married for 27 years. “We met over a woman’s gall bladder in the operating room,” Peter remembers. “All I could see were her eyes.” And the couple’s inclination to volunteerism has been with them from the start. Peter’s father, a World War II surgeon who worked at the Mayo Clinic for 30 years and once served as team doctor for the U.S. Olympic hockey team, always emphasized humanitarian principles.

“My father brought me up to give back to my community,” Peter says. “And I suppose my community has become more than just local. We help a few people for a short time—we’re not saving Africa or saving Haiti.” After a pause, he adds, “I always feel like I should stay longer and do more.”

“People sometimes say, ‘Oh, I could never do what you do,’” Patti Janes reflects. “But there’s nothing more important than your time and your touch. You don’t need a skill. Just your time and your touch. Even the people who have nothing, they’re all helping each other.” —Devon O’Neil

Face Value

Devinder Mangat, of the Mangat Plastic Surgery Center in Edwards, knows that in the post–Nip/Tuck era, many people think his medical specialty is a vanity-driven indulgence of the idle rich. And he derives great pleasure from helping people improve their physical appearance and consequently their sense of self-worth, regardless of their socioeconomic status.

Dr. Devinder Mangat (left) performs surgery in Belize.

But what really drives Mangat, a 64-year-old face and neck specialist who has been practicing in the Vail Valley for 17 years, is the reconstructive side of plastic surgery—returning function and restoring appearance to burn victims and people suffering from tumors, cancers, cleft lips and palates, and other congenital deformities. Whereas about 90 percent of Mangat’s work in the Vail Valley is of the cosmetic variety, 100 percent of the pro bono work he does in the United States and around the world is reconstructive.

“What, unfortunately, the press and the media have popularized in plastic surgery is the cosmetic surgery, or the surgery of appearance—and you certainly cannot discount the need for that and how fulfilling that is for both the patient and the surgeon,” Mangat says. “But you don’t hear as much about the need for those reconstructive procedures that, for the patient, are extremely valuable.”

A native of Kenya raised by Indian parents, Mangat heads up a surgical mission team for Horizon Community Church in Cincinnati—where he also has a practice—with which he travels to Orange Walk, Belize, every February. His team performs between 60 and 75 pro bono surgeries over a four-day period in the impoverished community, where cleft lips and palates—surgically repaired at an early age in the developed world—are common among children into their teens. The deformity can lead to speech problems, swallowing difficulties, drooling, aspiration of food into the nose, and other problems.

“There’s a great deal of social stigma attached to someone who has an unrepaired cleft lip, almost a mythological curse where these kids are ostracized and maybe thought to be possessed by the devil,” Mangat explains. “So to be able to give them a so-to-speak ‘normal life’ is really just tremendous.”

Mangat and his family split time about equally between their home in the Vail Valley, which they’ve had for 25 years, and their home in Cincinnati. But with two of his four children and two grandchildren living in Denver, and his overall love of the mountain lifestyle, Mangat says his family will be transitioning to the Vail Valley full-time in the next year.

“The mountains are much too drawing to your heart to be able to stay away,” he says. “I love the outdoors. I climb fourteeners [Colorado mountains with peaks of 14,000 feet or higher] and I bike and I run and I love to play golf, so Colorado is just one giant playground that I really enjoy.”

As president of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in the late 1990s, Mangat also helped found a two-pronged philanthropic program called Face to Face. One aspect of that national charitable organization parallels his work in Belize, sending plastic surgeons around the world to operate on children from India to Mexico. Another focus of Face to Face is a domestic program that works in conjunction with the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Once women are out of an abusive relationship, if they have facial deformities or scars, volunteer surgeons for Face to Face do reconstructive surgery on a pro bono basis.

“That really has two benefits: one is obviously the physical improvement, restoring a woman’s face to its pre-injury status,” Mangat says.

“But the second benefit is psychological, because many of these women believe this is closing a door on the past and moving on.”