Damned Canyon

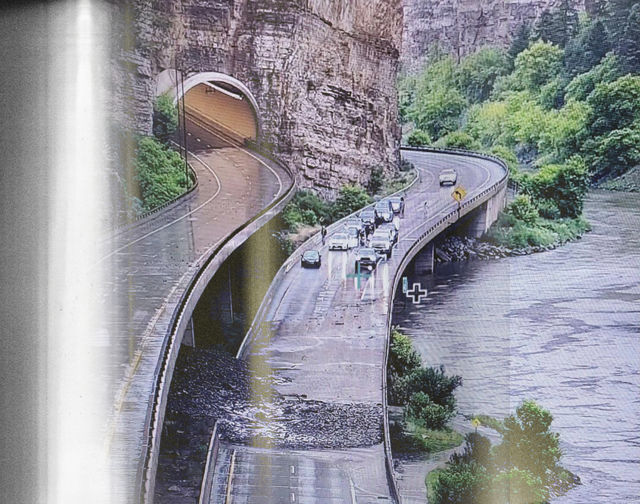

Debris field, July 23, 2021

In a summer of historic thunderstorms, this one was different.

It came from the south after most had come from the north. As its rain-soaked clouds steamed toward Glenwood Canyon on the afternoon of July 29, 2021, the National Weather Service (NWS) issued a Flash Flood Warning at 4:12 p.m., closing Interstate 70 through the canyon. The initial wave passed without incident, but it saturated the soil in advance of a substantially more powerful cell that blew in just after sunset. The NWS issued a second Flash Flood Warning at 8:45 p.m. By then, it was too late to evacuate everyone on the highway, so motorists sheltered in Hanging Lake Tunnel. Suddenly the heavens emptied, like a trap door opening from the bottom of a pool.

In the wake of the Grizzly Creek wildfire that torched much of Glenwood Canyon the prior summer, the US Geological Survey (USGS) had done extensive modeling on the likelihood and scale of debris flows across the burn scar, where the fire had weakened the hillside’s stability by killing the vegetation that kept the soil and rocks in place. The agency’s scientists calculated a threshold for how much rain it would take before the risk of a major debris flow became “high” or “very high.” Their estimated breaking point was a rate of one inch per hour for a period of 15 minutes.

Grizzly Creek Fire, August 14, 2020

The storm that hit the Grizzly Creek burn scar the night of July 29 would later be called a 500-year weather event. The Cinnamon Creek rain gauge measured 0.46 inches in a five-minute period, for a rate of 5.5 inches per hour—more than quintuple the USGS’s threshold and equivalent to the sky dumping nearly six feet of snow in an hour. At 9:54 p.m., the NWS upped its warning to a Flash Flood Emergency. The storm triggered spectacular debris flows on both sides of the canyon, seven of which crossed I-70; more than 100 motorists spent the night in the tunnel. A particularly massive flow rumbled down Blue Gulch at mile marker 123.5, blowing out the concrete barrier on westbound I-70 like it was plastic netting. Both east- and westbound lanes of the highway were buried.

“It was to another level than any of the past debris flows,” says Andrew Knapp, the Colorado Department of Transportation’s (CDOT) resident engineer in Glenwood Springs. “But it still wasn’t the main event.”

Only a small percentage of Blue Gulch’s soggy slopes ran the night of July 29—the rest was still clinging precariously to the 4,000-foot mountainside. CDOT cleanup crews almost had finished clearing the debris on July 31, and were close to reopening the highway, when another storm triggered a Flash Flood Warning at 3:50 p.m. An hour later, a gauge at East Fork of Dead Horse Creek recorded a peak rainfall intensity of almost triple the USGS threshold. The resulting debris flow in Blue Gulch dwarfed the July 29 slide.

“It jumped to a level that we hadn’t imagined,” Knapp says. “Total loss of eastbound I-70—just a pile of rocks. The overhang of the westbound lane was completely gone for 50 feet.”

I-70 mudslide, July 3, 2021

For months, experts had been waiting to see how the canyon’s geology would respond to the Grizzly Creek fire, which had closed I-70 for two weeks in August 2020. They’d seen hints of the destruction to come: a pair of large debris flows in late June on the west side, followed by larger slides on July 3 and 22 that blocked the road for multiple days. But the closure that began on July 29 set a new bar, stretching almost 16 days and upending life on both sides of the canyon. Local workers were left to commute over rugged Cottonwood Pass, with National Guard soldiers directing traffic. Tractor trailers detoured—glacially, illegally, and only sometimes successfully—over Independence Pass, backing up traffic into downtown Aspen.

Despite the substantial short-term headaches, however, a bigger question began to emerge: If once-generational natural disasters were to be a constant threat in Glenwood Canyon moving forward, what would happen to the primary highway linking Aspen and Glenwood Springs to Vail and Denver—and to life as locals had known it?

When CDOT project manager Ralph Trapani first traveled through 12-mile-long Glenwood Canyon, he was on his bicycle, pedaling along a dangerously narrow Highway 6 in the late 1970s. “I couldn’t imagine building a four-lane through there at that point,” says Trapani, who oversaw the construction of I-70 from Dotsero to Glenwood Springs starting in 1980 until it opened in 1992.

Before breaking ground, Trapani had his team bore into the earth to find out what its history was—and what they were building on. They discovered, among other things, a mysterious gray clay 40 feet below the surface (determined to be ash from an ancient eruption in Dotsero, home to a dormant volcano with a crater nearly half a mile wide and 1,200 feet deep) but nothing like what happened in Blue Gulch in July 2021. “We looked back 100,000 years,” says Trapani, now a consulting engineer, “and there was no evidence of those kinds of debris flows. And it would’ve been extremely obvious.”

Despite its challenging topography—2,000-foot walls plummeting into the Colorado River—Glenwood Canyon had been relatively stable since mechanized transit began, after the Denver & Rio Grande railway expanded its line from Red Cliff west to Glenwood Springs in 1887. The first vehicular passage came in the early 1900s on Taylor Wagon Road, a rugged dirt track punched through the bottom of the cliffs. Eventually, Taylor Wagon Road became US Highway 6, a paved two-lane highway with stripes down the middle but no shoulder. Fatal crashes were common, Trapani says: “Mostly head-ons or opposite-direction sideswipes.”

The lack of a safe route also affected recreation. Colorado River boaters, commercial and private, had to put in and take out at one of 60 informal gravel pullouts along the road. “Rafters were saying it’s dangerous to get off and on the highway, and we can’t make a living,” Trapani recalls. “Fishermen were saying there’s no decent fisheries, and you couldn’t ride your bike there.”

Despite all of that, the decision to send I-70 through Glenwood Canyon was no sure thing. Cottonwood Pass to the south and the Flat Tops to the north also were evaluated as potential alternatives in the early ’70s. Even in the face of the engineering challenges, a route through Glenwood won out, and in 1972 CDOT started detailed planning and conceptual design for what would become a $480 million project ($983 million in today’s dollars).

Environmental groups sued to stop it, to no avail. Out-of-work oil workers provided labor. The road’s design was cutting-edge, with almost all of it either elevated over the river or bored into the mountainside. “There are 40 bridges and three tunnels in 12 miles,” says Trapani, who still lives in Glenwood Springs. “That’s pretty unique. And the whole thing is a curve; you’re almost never on a straightaway once you get into the canyon.”

The road saw its share of rockfall over the years—boulders estimated at around 130,000 pounds hit the highway in 2004 and 2010—but rarely closed; if it did, it was usually open within hours. Everyone who worked the corridor, however, knew that a fire in or above the canyon would be bad.

At approximately 1:30 p.m. on August 10, 2020, vegetation in the I-70 median ignited one mile east of Glenwood Springs. Theories on the cause ranged from a discarded cigarette to sparks from a semi dragging tire chains, but the fire was generically designated as “human caused.” It burned a total of 32,632 acres (nearly 51 square miles), including 28,317 acres managed by the US Forest Service.

Despite there being 30 potential debris paths in the canyon, history showed they rarely if ever ran. Soon after the fire crackled, however, experts knew that was likely to change. The Forest Service brought in its Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) team earlier than usual to map out the risk of debris flows. The team identified structural weak points for CDOT, including a large path that threatened the Hanging Lake Tunnel Command Center, where up to 20 employees could be working. “We had estimates from the USGS that we could have anywhere from 5,000 cubic meters of debris up to 500,000 cubic meters flowing down this drainage. And we had just a three-foot pipe to handle those flows,” says Knapp, the CDOT engineer. “The historic channel went right to the back door of our facility.”

CDOT decided to build a diversionary berm above the command center with rock and dirt left over from tunnel construction. If not for the berm, Knapp says, the center likely would have been destroyed by the 2021 flows. Nine rain gauges were installed at various points in the canyon to help the National Weather Service and other agencies monitor storms. One thing became clear as CDOT analyzed models of potential flows and how to mitigate them structurally: if Blue Gulch went big, nothing could or would stop it.

“What our consultant said,” Knapp recalls, “was to not install mitigation at Blue Gulch, because the energy levels were so high from a potential event.” He pauses. “We knew we had problems on our hands, but we didn’t expect something to this extent.”

The 15.5-day canyon closure last summer hit Garfield and Eagle counties like a border wall. Those who lived in Garfield County and had jobs in Eagle County, or vice versa, suddenly had to drive up to two hours instead of 20 minutes to get to work. “Fifteen to 20 percent of our employees live in Garfield and commute to work here in Eagle,” says County Manager Jeff Shroll. “My entire fleet crew, who fix all our vehicles, buses, heavy equipment, and snowplows, lives in Garfield County. Same with a lot of our road and bridge guys. You can’t remotely plow a road.”

Eagle County Manager Jeff Shroll

Image: Ryan Dearth

This was not to mention doctors who practice in both valleys or cancer patients who needed treatment at the Shaw Cancer Center in Edwards. “I knew this stuff, but I didn’t know it until we had the big closure,” Shroll says. “You’re just like, holy smokes.”

For communities west of the canyon, the fire and mudflows took an even greater toll. Grizzly Creek and No Name Creek historically supply pristine drinking water to tens of thousands of residents downstream, starting with the City of Glenwood Springs. The debris flows, however, created unprecedented levels of turbidity, or sediment in the water. “We had a couple turbidity levels that were so high they were not readable by any devices,” says Bryana Starbuck, the city’s public information officer. Glenwood Springs spent $3.4 million on water plant infrastructure improvements after the fire to protect its system from sediment-laden water. “Those improvements, and round-the-clock work from our water team, were the only things that allowed us to continue producing water for our community throughout these high-turbidity events last summer,” Starbuck says.

Middle Colorado Watershed Council Executive Director Paula Stepp

Image: Ryan Dearth

Paula Stepp, executive director of the Middle Colorado Watershed Council, which includes Glenwood Canyon, is a Glenwood City Council member and a 40-year local. She stayed in close contact with communities downstream as the debris flows grew bigger. “I just remember people going, What’s next? Grasshoppers? Biblically. There has to be another blow,” Stepp says. “Dark humor started to come through.”

Hanging Lake, a popular attraction in the heart of the canyon, was miraculously spared by the fire but not by last summer’s mud, which destroyed its access trail. The Forest Service isn't planning to reseed the burn, because much of the topography is too steep, and the area is recovering on its own. Though they were separate events, when engineers attribute a cause to the fire and subsequent mudflows bedeviling the canyon highway, they often use the same two words. “I’ve probably spent more time in Glenwood Canyon than any other scientist or engineer, and in my view this natural destruction is almost all caused by climate change,” Trapani says. “I feel that’s a definitive statement.”

So, what now?

As of mid-April, Ken Murphy, whose company H20 Ventures operates the concession for reservations and staffing at Hanging Lake, was still waiting to learn when visitors would be allowed to return. Last year’s devastation canceled 15,000 reservations. At a max of 615 guests per day paying $12 each, the three-month peak season brings in $680,000—only the start of Hanging Lake’s $4.6 million economic impact to Glenwood Springs. They will scale a temporary trail this year, but in March the nonprofit Great Outdoors Colorado donated $2.2 million to the City of Glenwood Springs and the National Forest Foundation to build a permanent replacement.

The canyon’s recpath is expected to reopen this summer, too. And while this story went to print before the Colorado’s peak runoff season had given the river its summer shape, boaters were cautiously optimistic that the classic canyon runs would still be themselves, albeit with some shallower holes. A return to normal would be especially welcome in Glenwood Springs, where some shops reported 50 percent less business during last summer’s road closures.

No one has seriously discussed abandoning I-70 through the canyon for a different road, but officials on both sides have been working to improve alternate routes in case of additional closures this summer. Cottonwood Pass, a rural dirt road that tops out at 8,500 feet, went from seeing just a handful of vehicles per hour to gridlock in both directions last August. Travelers struggled to navigate its blind curves and steep grades. Shroll says it would cost about $30 million to improve Cottonwood enough that it could stay open year-round. Regardless, he concedes, it will never be “the end-all solution.”

On the optimistic side, Glenwood Canyon’s time in limbo could be finite. “From talking to the subject-matter experts, we can expect this elevated debris-flow hazard to persist for about five years,” Knapp says. What happens in those five years will determine the course of history. Geologically, the threat remains of a “debris-flow recharge,” wherein the over-steepened channel erodes until it slides. “We’re not naïve enough to think it’s not going to happen again,” Knapp says. “We’re just hopeful it won’t be as severe.”

Trapani, 70, who in addition to his work in Glenwood Canyon oversaw the original inspection of Eisenhower Tunnel and helped build I-70 over Vail Pass, likes to remind everyone that maintaining an interstate through the Rocky Mountains is not guaranteed. “I know that civil engineers think they can challenge Mother Nature and win, but the corridor is only open because she is letting us keep it open,” he says. “If she wants to close that road, she will whenever she wants.”

As she did in late April, when the interstate again was shuttered in both directions after a wildfire erupted east of the canyon at milepost 137 and consumed nearly 100 acres of riverbank vegetation, stopping mere yards from the City of Gypsum’s westernmost homes.

But perhaps that was just a reminder, and Mother Nature will instead show mercy. Because if the last two years have proved anything, it’s that Glenwood Canyon supplies vitality to a local population that needs it—now more than ever. “We have to find a way to keep our valleys connected,” Shroll says, “because we are so connected.”

How to Help Recovery Efforts in the Canyon

Ten days after the Grizzly Creek Fire started in August 2020, anticipating a yearslong effort to repair the blaze’s damage to trails and recreation sites, the nonprofit Roaring Fork Outdoor Volunteers (RFOV) created a working group called the Glenwood Canyon Recreation Alliance (GCRA) alongside public and private partners. One of the group’s primary goals was community-led restoration of trails and other areas affected by the fire.

Though a crew conducted work on the Jess Weaver and Grizzly Creek trails prior to the July 2021 debris flows, its charge changed dramatically after those events. The Grizzly Creek Trail sustained significant damage around the 2.75-mile mark, as well as further up the drainage. Some of the debris chutes were 25 feet wide and 20 feet deep, says Jacob Baker, RFOV’s director of communications and strategic partnerships. Across the canyon, 20 to 30 percent of the 1-mile-long, 1,000-vertical-foot Hanging Lake Trail was destroyed, leaving the trail in need of a multiyear rebuild.

RFOV contributed some 720 volunteer hours toward improvements in the canyon last summer, and Baker expects to add to that total this year. Interested in joining the cause? rfov.org