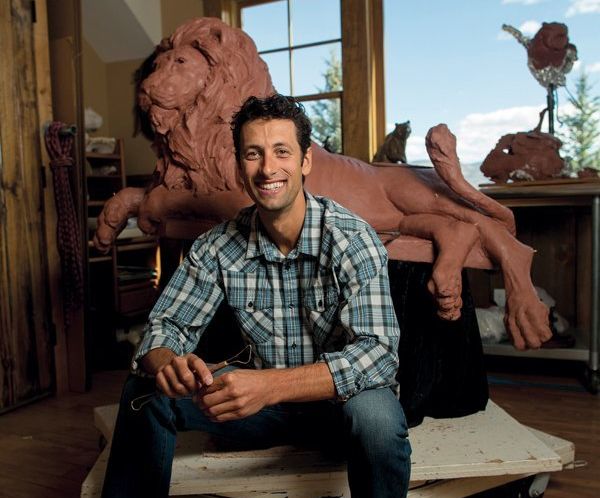

Lion in Winter

Sculptor Jesse Horton in his Lake Creek studio with his latest work, a leonine study of power and restraint

Image: Dominique Taylor

On March 28, 2010, fresh from transiting the South Pacific in a primitive Polynesian sailing canoe, Jesse Horton was in the southern hemisphere preparing to leave on yet another adventure. But then his mother phoned with devastating news: his father, the much-loved Beaver Creek sculptor Walt Horton, had died unexpectedly in his sleep. Jesse canceled a 32-mile sea-to-summit trek through New Zealand’s Fiordland National Park and flew home to Colorado.

But there wasn’t time to properly grieve.

At 60, Walt Horton had been at the pinnacle of a brief but prolific career. In the mid-1990s, he had relocated his family to Edwards from Bermuda, where he would spearfish and free dive with his sons while eking out a living as a cartoonist for the island newspaper. Returning to his Colorado roots in his mid-forties, Horton first put hands to clay and found a new voice, translating his gift for storytelling into three dimensions as a sculptor. His whimsical bronzes of mice, bears, and children include Repentance, a life-size rendition of an aggrieved grizzly with an arrow in its backside nose-to-nose with a Native American boy guiltily clutching a little bow behind his back, which for years was a Beaver Creek public fixture. Commissions were pouring in, to the extent that Walt and his wife of 40 years, Peggy, had opened a gallery (Walt Horton Fine Art) in Beaver Creek Village just five months earlier. The free-spirited Horton had no golden parachute; as Peggy explains, “His life insurance was his art.”

That fateful spring, sculptures that had been paid for remained unfinished in his airy atelier in the family’s Lake Creek home overlooking New York Mountain. The night he died, the artist had broken one down, a nearly completed clay rendition of the biblical Ruth; 15 copies had been ordered, and Walt, ever the perfectionist, had elected to rework it according to some plan that died with him. In addition, Peggy had written a children’s storybook based on Repentance, and Walt had yet to illustrate it. It was up to Jesse, who had learned to draw and sculpt at his father’s side but had other plans for his life (namely, global travel like that of his younger brother, a photographer for National Geographic), to finish Ruth, illustrate the book, and complete a backlog of other works so that Peggy could pay the Lake Creek mortgage and the Beaver Creek gallery rent.

“It was overwhelming,” says the younger Horton, now 35, something of a lost wax copy of his father as a young man: strikingly handsome, six-foot-something, lithe and athletic with a full head of curly black hair, playful brown eyes, and a mischievous smile. “To embark the way I did upon what since has been a new career for me, something that was completely unintentional ... it was just an emotional roller coaster for me, but it also was a very healing opportunity to still connect with him. I look at his sculptures every day, and I see his personality in them in ways that I never saw before.”

Horton completed all that had been left undone, channeling his father, using Walt’s favorite modeling tool. Finding impressions with his fingers that his father had made with his own was cathartic; he felt Walt’s gentle presence, teaching him, working through his hands, and when feeling lost would sometimes gaze up at the ceiling in frustration, beseeching, “Hey, if you’re out there, I could use a little help here!”

At home, Horton worked in the living room because he couldn’t bring himself to inhabit his father’s studio, which remained essentially as Walt had left it on March 28. As days added into weeks and weeks multiplied into months and months turned to years, the second-generation sculptor eventually found his own voice and his own audience. The day he began thinking of himself as an artist was the day he began sculpting in his father’s studio.

There’s nothing whimsical or Walt-like about Horton’s latest endeavor, a half-size lion frozen in brick red oil-based clay, confidently commanding a pedestal in the center of the Lake Creek atelier. Conceived months before the shooting of Cecil the Lion provoked worldwide outrage, the sculpture is not meant to evoke contempt for hunters (Horton himself is a bow hunter who moonlights locally as a hunting guide); it’s a study of restraint, of the wisdom and strength of someone in authority who possesses overwhelming power yet elects not to wield it.

“You can look at my father’s pieces and know it was him because they have his voice, his fingerprints on it,” says Horton. “I spent a lot of time worrying about what style I was going to have, but last year I realized that it doesn’t matter. To leave that and not worry about it anymore really helped me progress.”

And for someone who once sailed a replica vaka canoe from Polynesia to Hawaii, steering off the stars in the manner of an ancient mariner, progress is measured in advances and retreats. Just as his father did, Horton often breaks down a nearly finished work in clay and begins anew, like a Tibetan monk casting the sands of an intricate mandala to the wind.

“You can’t be afraid to take a step back, even though it hurts,” he explains. “It ties into celestial navigation: that process in a journey of taking a step back seems counterintuitive, but if you know where you’ve come from and you know where you are, it allows the next steps to be intentional and progressive, rather than saying a Hail Mary and hoping you land somewhere safe.”

These days, whenever he needs inspiration, Horton puts down his father’s sculpting tools and returns to his former life of adventure. Sometimes he’ll disappear for weeks, if not months, serving as first mate on a 72-foot sailing yacht that has circumnavigated the globe or piloting a deep-sea submersible in Costa Rica, where he also maintains a home. Wanderlust sated, he always returns to his father’s studio, where an altogether different sort of adventure awaits. Recently, he crossed the threshold in Lake Creek hefting a 15-inch-high bronze freshly freed from the mold, a sculpture of a draft horse named Calvin that grazes off Lake Creek Road. He took an interest in the animal after its owner died and it was almost put down, noting over time that the Shire had a personality, and he began sketching, then working clay. The bronze Calvin is turning its head, quizzically considering the presence of a sparrow perched upon its haunches. This is pure Jesse Horton, with the humility and subtle humor of Walt Horton, acknowledging the debt he owes to his lost muse and mentor.

It’s called Hitchin’ a Ride.