How to Use Your Epic Pass to Visit Europe's Vail Valley

My wife and I are Epic Pass holders. We’re also parents with a tenuous hold on a surly, bond-breaking teenager who in 2017–18 took a junior year sabbatical from Battle Mountain High in Edwards to study German at Maria Ward Schule, an all-girls public school in Landau in der Pfalz, a rural town surrounded by vineyards near the French border of southern Germany.

So as a prelude to a two-week family reunion in Landau last March, we reserved a room at the Hotel Sandhof, a boutique inn in the heart of Lech, Beaver Creek’s Austrian sister resort, which provides US Epic Pass holders who book three consecutive nights of lodging with as many free lift tickets to the Cradle of Alpine Skiing. And as a side trip on the road from Landau to Lech, we also booked two nights at the Sonnenalp Resort, a five-star vacation hotel owned by the Faessler family (proprietors of Vail Village’s Sonnenalp Hotel) where Mikaela Shiffrin stays when she races in Ofterschwang, a World Cup downhill in Bavaria’s Allgäu Alps.

A few hours after checking in with our daughter in Landau, we roll to a stop beneath the broad porte cochere outside the Sonnenalp in Ofterschwang im Allgäu just before the final dinner seating. At night the resort—with 225 rooms stacked in five stories cloistered around a glass atrium housing a pool and a fitness complex—gleams like a stately luxury liner steaming across a dark ocean.

Inside, our voyage begins.

Sonnenalp Resort, a wintry oasis in Bavaria’s Allgäu Alps

Image: Courtesy Sonnenalp Resort

Entering the elegant reception area, we’re welcomed with flutes of prosecco and relax in the lobby bar as our table is readied, admiring the Titanic-like grand staircase and wraparound balcony, the flagstone floor, the mechanical clock clacking above the fireplace, the wrought iron chandelier with 80 electric candles illuminating an oak-beamed ceiling frescoed like the sky with bunting-shrouded family crests floating among the cumulus. At 8:30 p.m., the main dining room—eight themed parlors and two specialty restaurants (including the Michelin-starred Silberdistel) with seats for more than 400—buzzes with multiple dialects of German; the vast majority of the hotel’s clientele are Germans (Munich is as close to Ofterschwang as Denver is to Vail) who come to ski in the winter and golf in the summer and stay, on average, six days. As at most European luxury hotels, accommodation includes half-board meals—breakfast and dinner. Ours arrives in six courses, each a verse in an artistically plated culinary composition—North Atlantic char with cauliflower and coconut crumble, carpaccio with dumplings, Bavarian beef consommé, Allgäu trout in a pinot blanc sauce, Rindershmorbraten (Bavarian beef pot roast) in a red wine sauce with spätzle, and an unforgettable roasted plum canelé (a French pastry with rum and vanilla custard in a delicate crust caramelized like crème brûlée)—all paired with regional wine selections, from the resort’s private-label grüner veltliner to an exquisite weissburgunder from a vineyard on the Bodensee 90 minutes west. Sated, we wander through the hotel, stopping to ogle the darkened windows of a dozen boutiques in the shopping arcade, and retire to our junior suite.

The Sonnenalp's main lobby

Image: Courtesy Sonnenalp Resort

We wake to a world of light and birdsong. Throwing open the curtains and glass doors, in plush robes we step out onto our garden patio and walk barefoot on the dewy lawn, staring agape beyond the emerald fields at a horizon ragged with white-capped peaks brilliant against an azure sky: Bavaria’s Allgäu Alps. Although Ofterschwang sits in a valley that’s a third the elevation of Vail, the landscape reminds us instantly of home. After the breakfast lover’s version of Augustus Gloop’s swim in Willy Wonka’s chocolate river—a buffet with magnums of Champagne, juice from a machine fed by a hopper of whole oranges, 22 types of sausage, lox and trout caviar, 14 varieties of cheese from a creamery a 10-minute walk away, 22 types of oven-warm bread and buns paired with local butter and as many types of jam, two-dozen different versions of muesli, a dozen varieties of pastry—it’s nearly time for my audience with Michael Faessler, the resort’s proprietor.

From a photo gallery off the main hall (and the hotel’s website), I learn: in 1919, Adolf and Eleanor Faessler, with help from their son and daughter-in-law (Ludwig and Resi), converted an old farmhouse with eight cows into a country inn, adding guest rooms, a dining room, and a spa; after Adolf and Eleanor retired in 1932, Ludwig and Resi registered the Sonnenalp name and expanded the inn into a hotel with 80 more rooms, a swimming pool, tennis courts, and a sauna; following a tragic fire three years after Ludwg and Resi retired in 1964, their son Karlheinz (and wife, Gretl) rebuilt the resort to its current footprint, adding still more rooms and amenities (including Germany’s first hotel golf course); in 1968, six years after Pete Seibert did the same in Vail, Karlheinz, an Olympic ski racer, built the first ski lift to the Ofterschwanger Horn (the summit of the local mountain) and founded the first hotel ski school in Germany; in 1979, Karlheinz purchased and renovated a tired motel next to the covered bridge in Vail and in the 1980s dispatched his youngest son, Johannes, to manage the property; in 1989, Karlheinz handed off operation of Bavaria’s Sonnenalp to eldest son Michael, who, in addition to managing a staff of 500 with wife Anna Maria, now oversees World Cup racing (which Karlheinz brought to Ofterschwang in 1997) as well as a complete renovation of the resort for its 100th anniversary in 2019.

A Sonnenalp dessert

Image: Courtesy Sonnenalp Resort

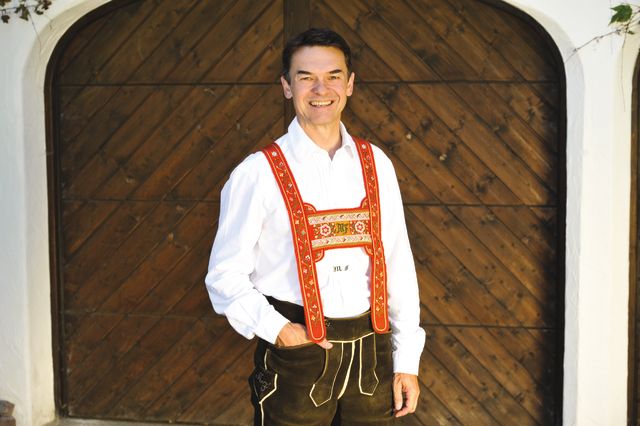

Dashingly handsome and immaculately coiffed, the fiftysomething hotelier greets me outside his office, and we settle on a banquette on the balcony as guests scurry about the reception hall below, off to ski school; tennis, golf, and riding lessons; spa treatments; water aerobics classes; or a countryside rally in one of the hotel’s four high-performance Audi sports cars available to guests.

Sonnenalp Resort's Michael Faessler

Image: Courtesy Sonnenalp Resort

“This place is like a big cruise liner,” says Faessler, projecting the bearing of a ship’s captain in the Sonnenalp’s traditional uniform of dark wool blazer with an upturned leather collar and hand-tooled buttons. “There’s nothing around except the mountains and nature. Whatever you find here, the services—the shops, the stables, the ski school—we do it ourselves, with our own people. Nothing is outsourced.”

In the early 1980s, while his younger brother, Johannes, finished hotel management school at the University of Denver, Michael Faessler ran Vail’s “Kleine Sonnenalp,” as it’s known in Germany, for a season.

“We are two brothers, and we both wanted to be in the hotel business, but we only had one hotel,” he explains. “My dad was a ski racer in the Olympics in Cortina, and he was injured and couldn’t race, but he has a lot of friends who were ski racers. Some of them, like Pepi Gramshammer, ended up in Vail. This was the connection to Vail. He thought, ‘This is the place to be, to build a second hotel.’”

Mikaela Shiffrin's World Cup win in Ofterschwang

Given its remote location in Bavaria’s Allgäu (a dairyland on the Austrian border that reminds me of the Wisconsin Dells) and the diminutive stature of Ofterschwang’s ski area—just seven lifts serving 15 trails with a summit elevation of a mere 4,613 feet, (compared to Vail’s 31 lifts, 193 runs, and 11,570-foot summit)—Sonnenalp Bavaria rarely hosts, or figures in the travel plans of, skiers from Colorado. Except for one weekend in March: World Cup racing. In fact, we had just missed Mikaela Shiffrin and her mother/coach/manager Eileen, as well as the Mikaela Shiffrin Fan Club, which traveled to Ofterschwang to witness the Eagle-Vail superstar win her second consecutive overall World Cup title the weekend before our arrival.

“She stayed here,” Faessler confirms. (Indeed, following her stay here Shiffrin posted a half dozen photos to her Instagram feed, vamping with the mannequins in the shopping arcade and looking radiant at a table in the Victorian-themed dining parlor.) “She always stays here. It’s a little bit of home.”

Our time likewise passes in a blur of hiking, feasting, and relaxing. Upon checkout, we’re gifted with a paper-wrapped loaf of multigrain bread hot from the oven. Before leaving Ofterschwang, we park at the ski hill—the base area, still decorated with World Cup posters and bunting, is all but deserted—and purchase tickets for a scenic ride up the Weltcup Express. Just below the summit of the Ofterschwanger Horn, in shirtsleeves on an unseasonably warm spring morning, we dodge skiers as we trudge across corn snow to visit the Sonnenalp’s Weltcup Hütte; hanging on a wall of fame inside the cozy chalet, we discover a framed photo from the 2001 Women’s World Cup, a beaming Karlheinz Faessler sandwiched between Vail Valley locals Kristina Koznick (a three-time Olympian who now plays hockey with the Vail Breakaways) and four-time Olympian Sarah Schleper wearing a Vail Resorts-branded headband.

On the ride back down, beyond the empty bleachers of the finish stadium, a breathtaking panorama unfolds before us: In the distance, the morning sun refracts off hundreds of glass panes on the Sonnenalp, which gleams like a multifaceted jewel swaddled in emerald velvet. From our seat in the sky, out on the horizon and seemingly close enough to reach out and touch, beckon the craggy Austrian Alps, our next destination.

From the air, Lech looks much like Vail did when the resort was founded in 1962: a two-lane highway following the course of a river winding through a valley surrounded by peaks, a skier’s paradise.

Leaving the springtime greenery of Bavaria’s Allgäu behind us, the two-lane highway switchbacks ever upward into Austria before diving into the mouth of the nine-mile-long Arlberg Road Tunnel; dwarfing the Eisenhower, for two years at the end of the 1970s this was the world’s longest. After what seems like an hour of midnight, we slingshot out the other side, blinking like Lucy and Edmond emerging from C.S. Lewis’s magic wardrobe into a Narnia-like winter realm. This alpine kingdom is crisscrossed with tramway cables connecting one medieval mountain village after another, a world of fog and sideways-blowing snow where the thermometer registers 30 fewer Fahrenheit degrees than it did atop the Ofterschwanger Horn perhaps 25 miles, as the eagle flies, to the north. From the chic resort towns of St. Anton and St. Christoph, the road corkscrews up the Flexen Pass (where the highway is roofed to shed avalanches), then drops into the tony village of Zürs (favored by Princess Caroline of Monaco and Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands) and then finally, at the pinnacle of Arlberg Alps yet more down-to-earth, Lech (where Princess Diana wintered).

It’s easy to see why Lech was once named Europe’s most beautiful village. Following the course of its namesake river, it’s a singular promenade, a milelong procession of pedigreed hotels and restaurants and shops interspersed among ski lifts and tramway stations. Upon our arrival shortly after the lifts have stopped turning, Lech is a riot of hale Europeans shouldering skis or freshly divested of skis, strolling in their après finest to slopeside lounges on both banks of the river.

Our hotel, the Sandhof, occupies a respectable niche near the center of it all. It’s classically Lech. Family-owned by Martin Prodinger, who grew up in the hotel his grandfather founded in 1933, it boasts four floors of guest rooms atop a basement ski locker room and a main-floor social hub with a tiny reception desk and cubbies for 29 keys, a dining room with 29 tables, an excellent wine cellar, and a cozy living room/library/bar where a pile of logs crackles in a hearth and guests linger around tables with cups of cocoa, snifters of brandy, and tall draughts of Arlberg’s signature beer. As my wife freshens up for dinner in our room (facing a postcard-perfect composition of the Austrian ski resort: gabled rooflines loaded with meters of snow, the onion-domed steeple of Lech’s 14th-century parish, the twin cables of the Rüfikopf seilbahn disappearing into snow-laden clouds), I settle onto a stool at the hotel bar, helmed by our innkeeper, who welcomes me with a frothy pint of Frastanzer pils.

“The good thing about being a hotelier here is that you always have happy and friendly people around you,” says Prodinger, a graduate of a hotel management school in Salzberg dressed in the Sandhof’s uniform: pleated trousers with a plaid wool vest over a starched white shirt monogrammed with the logo of Ski Club Arlberg, the world’s oldest alpine club, founded in Lech in 1901. “It’s not like being a lawyer or a dentist or a doctor looking after sick people. People are always in a good mood. It’s nice to help them be happy. It’s easy. It’s not a big thing.”

Nordic skiers on the banks of the Lech

I mention that we’re visiting from Beaver Creek, Lech’s sister resort, a North American alpine paradise nicknamed Happy Valley because it’s akin to living in Disneyland, the Happiest Place on Earth. Polishing glassware with a towel, Prodinger nods knowingly.

“Lech, it’s very small,” he says, estimating that the combined year-round population of the villages of Lech, Zürs, and Oberlech is 1,800. “Nearly everybody knows everybody, and everybody looks after everybody more or less. It’s a small world. If you have grown up here, it’s easy to handle. But it can be difficult if, like my wife, you are not born here and you marry somebody or you move here. There is a big up and down between the seasons. In May, no hotels are open, the restaurants aren’t open, so the place that you meet is in the post office or the grocery store.”

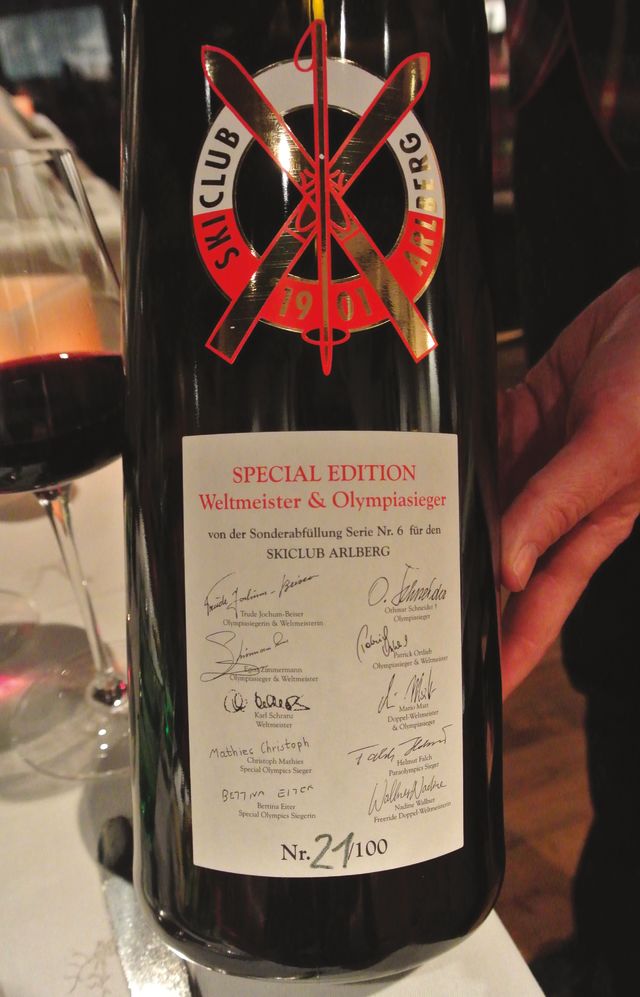

A magnum of Austrian red signed by World Cup and Olympic champions at the Sandhof.

Image: Ted Katauskas

I ask Prodinger about the black-and-white photographs hanging on the walls of the dining room and lounge. It’s his family history, he explains, and he takes me on a wall-by-wall walking tour, talking about growing up in the hotel, attending school at the onion dome church outside our room. In one photo, his grandfather, a butcher who laid the foundation of the hotel five years after the first lift in nearby Zürs was built in 1928, poses on the banks of the Lech in summer with fellow members of the Trachtenkapelle (the village’s brass band, which annually plays at Beaver Creek’s Birds of Prey races and the resort’s Oktoberfest celebration). In another, from the 1930s, the new hotel is buried in snow and Prodinger tells the story of how the mayor of Lech referred guests who arrived by train only to hotels that helped shovel the main road. Another shows 1964 Olympic gold medalist (and Ski Club Arlberg member) Egon Zimmerman, airborne in a full racer’s tuck soaring perhaps 30 feet above a vintage Mercedes coupe parked on the street, which is a roofless white tunnel with snow piled 10 feet high on either side (the resort averages 27 feet of powder each winter).

At our assigned table at dinner that night (consommé with fried sweetbreads, curried Guinea fowl in a lentil ragout, braised veal with potato pureé in root vegetable cream, banana splits), Prodinger fills our glasses from a special-edition magnum of Austrian red bearing the crest of Ski Club Arlberg that’s signed by the club’s World Champions and Olympians, a privilege that’s reserved for members, many of whom are seated in the room. As visitors from Lech’s sister resort, at least on this evening, we’re honorary members of the club.

We wake to a powder day—six inches of new snow, with more forecast—and clump across the street to Lech’s ski school to meet our guide, Daniel Martin, a ruggedly handsome young Austrian with chiseled cheeks and jaw and piercing blue eyes. After 10 years of 80-hour weeks as a mergers and acquisitions attorney, Martin quit Innsbruck to embrace life as one of the few who claim the mountains of Lech as their home.

A guest room at the Sandhof.

Image: Courtesy Hotel Sandhof

We ride the Schlegelkopf lift to a midmountain terminal that houses a chic new restaurant of the same name dedicated to the cuisine of Lech’s sister resort (celebrating Beaver Creek’s not-exactly-roughing-it ethos notably with an 82 euro ($95) imported US tomahawk steak paired with a 98 euro ($114) pour of scotch). From there we ride another lift to the 7,129-foot summit of the Kriegerhorn, then ski 220 (a blue run; the trails here have numbers, not names) to yet another lift that takes us to the Zuger Hochlicht, a dome of snow that, at 7,798 feet, is the highest point in Lech. There, the clouds briefly part, revealing the Everest-like peaks of the Mohnenfluh and the Braunarlspitze, an achingly beautiful sight we regard in silent reverie.

Martin tells us about Johann Muller, a local priest who in 1894 mail-ordered a set of skis from Sweden and transited from his snowbound village of Warth to Lech, an expedition that’s commemorated every year with the Run of Fame, a 53-mile ski race over three passes with an elevation gain of nearly 60,000 feet traversing the entire resort known as Ski Arlberg, Austria’s largest. With 88 lifts and tramways connecting seven ski villages—more than 180 runs offering as many miles of on-piste skiing, and 124 miles of off-piste terrain—it’s possible to ski for a week here and never retrace your tracks; Martin tells us that his clients, on average, hire him for 14 days.

Hotel Sandhof's lobby bar.

Image: Courtesy Hotel Sandhof

As quickly as the clouds parted, like a curtain they close then descend, shrouding the Mohnenfluh, the Braunarlspitze, then the peak we’re standing on. Attempting to outrace the fog, we’re off, chasing our guide’s ski tails, floating on soft snow through a whiteout more vertigo-inducing than a blizzard in the Back Bowls. Skiing through the clouds, this day we will cover all of Lech, in heaven.

At noon, sharing a tram car with dozens of skiers packed as tightly as commuters on a Tokyo subway, I ask Martin (who spent a season as a ski instructor in Aspen and visited Beaver Creek as a sister-city delegate during the World Championships in 2015) if he has any advice for skiers from Colorado.

“Forget your Americanism,” he says. “Forget your healthiness; forget your diet. Don’t eat Caesar salad. Eat a proper Austrian dish, poor people’s food for farmers who needed a lot of energy from as few ingredients as possible. There is no other place in the world where you will get as good a lunch as you will here.

“In Lech, lunch is more important than dinner. Most people here, they only ski until lunch, and your lunch lasts two hours and after two bottles of wine, you ski down to the spa. Especially in this weather, you barely see anybody on the slopes after 2 o’clock. This is what it’s about. Enjoy life while you are here.”

And we do just that.

A family on the trail from Lech to Zug.

The next morning, another powder day, we ski the resort’s quintessential run, Der Weisse Ring (“The White Ring”), a 14-mile-long trail connecting four villages, transiting six lifts, with 18,044 feet of vertical that attracts a thousand endurance skiers when the course is raced in January. Heeding Martin’s advice, we lunch at the Kriegeralpe, a mountain hut resembling a snowbound cuckoo clock, where, in a rustic dining room with thick panes of frosted glass and low, rough-hewn beams, we sup gulaschsuppe followed by grilled veal sausage with bacon-and-egg-laced fried grated potatoes, and ragout of local venison with spätzle and cowberries, paired with a bottle of Austrian weissburgunder.

Stashing our skis at the Sandhof, at the suggestion of the innkeeper’s wife, we set out on a two-mile hike to the nearby village of Zug to have coffee at the Gasthof Alpenblick—and a slice of what we are assured is the best apfelstreusel in Austria. We stroll through the center of town and cross the Tannenbergerbrucke, a covered bridge over the Lech River that could be a model for Vail Village’s (only this one’s 400 years older), then merge into a crowd crunching through the snow—high-cheekboned socialites in furs walking stately hounds, parents pulling rosy-cheeked babes bundled in wooden sleighs, silently gliding Nordic skiers exhaling clouds of steam—following a riverbank wanderweg through an old-growth evergreen forest. A few flakes fall, then more, and still more.

Under the dome of a snow globe, the scent of pine wafting on the wind, the Lech murmuring in its banks, hand in hand with my wife of 22 years, I think of the quote from Twain the Prodingers have painted on the paneling of the Sandhof’s dining room: Gib jedem tag die chance der schönste deines lebens zu werden (Give every day the chance to be the best of your life).

We did, and I think perhaps it was.

In Zug, we’ll arrive at the Alpenblick moments too late and find only crumbs remaining on a silver platter. But the journey to that place, that moment in time, I’m sure was sweeter. From a distance of months and more than 5,000 miles, I’m still savoring it today.

Stay

Hotel Sandhof

Dorf 124, A-6764 Lech am Arlberg, Austria

+43 5583 2298; sandhof.at

Double occupancy rooms from €290 ($337), includes breakfast and dinner, plus two complimentary lift tickets per day for US Vail Resorts Epic Pass holders who book three consecutive nights of lodging (epicpass.com)

Sonnenalp Resort

Sonnenalp 1, 87527 Ofterschwang, Germany

+49 8321 2720; sonnenalp.de

Double occupancy rooms from €470 ($546), includes breakfast and dinner

Sonnenalp Hotel

20 Vail Rd, Vail Village

866-284-4411; sonnenalp.com

Double occupancy rooms from $455

Ski

Bergbahnen Ofterswchwang Gunzesried

Panoramaweg 7, 87527 Ofterschwang, Germany

+49 8321 67030; go-ofterschwang.de

Adult single-day lift tickets: €38 ($44)

Ski Arlberg

Hnr 200, A-6764 Lech am Arlberg, Austria

+43 5583 2824; skiarlberg.at

Adult single-day lift tickets: €54 ($63)

More Info

Gästeinformation Ofterschwang

Kirchgasse 1, 87527 Ofterschwang, Germany

+49 8321 82157; hoernerdoerfer.de/ofterschwang

Tourismus Lech

Dorf 2, A-6764 Lech am

Arlberg, Austria

+43 5583 2161; lech-zuers.at