Remembering Pepi Gramshammer, A Vail Legend: Aug. 6, 1932 - Aug. 17 2019

When Pete Seibert and Earl Eaton first ascended Vail Mountain in 1957—five years before the resort opened to great acclaim—they approached from Highway 24 via Two Elk Creek south of Minturn, skied up the drainage to High Noon Ridge between Sun Up and Sun Down bowls, then descended to Highway 6 on Tourist Trap and lower Mill Creek.

Not that anything had a name back then.

Vail and its trademarked Back Bowls might be famous around the world today, but when the resort’s founders stumbled upon those vast snowfields, everything they beheld was as anonymous as the peaks of the Cascades were to Lewis and Clark. Over the decades, entrepreneurs, ski patrollers, and influential residents attached monikers to everything from the mountain itself (named for Charles Vail, a state highway engineer who routed the present-day interstate over his namesake pass) to the trails, lifts, decks, and restaurants that define it today. Beaver Creek, which opened 18 years after Vail, likewise was a tabula rasa when its ski trails were mapped in the 1970s. In some cases, the names that stuck honor individuals who were integral to the valley’s development; others reference an inside joke, or some forgotten moment in time.

To add a few layers of meaning to your favorite runs and places, we interviewed Vail and Beaver Creek notables who inspired, or named, landmarks at both resorts.

Pepi Gramshammer

One of Vail Village’s original residents, Austrian Olympic ski racer Pepi Gramshammer, now 86, opened Hotel Gramshammer in 1964, where he still lives with his wife, Sheika.

Pepi: When I got to Vail in April 1962, there was nothing here. I had turned pro when I went to Sun Valley after the Olympics in Squaw Valley, and there was a pro race at Loveland, which is why I came to Colorado. I won that race, and Pete Seibert and Bob Parker picked me up and drove me to Vail. There were still trees on Pepi’s Face then.

Sheika: It was January 1962. Pepi had met some founders of Vail in Sun Valley, among them Dick Hauserman, and they told him about the new resort they were involved with in Vail. They wanted him to race for Vail on the pro circuit, which had just started. After the Loveland race, they brought him to Vail to show him the mountain. They took him up and spent the night in a wood shack for sheepherders [who] used to bring their sheep over here in the summer until the late ’60s.

The next morning, they got up early and it was powder—unbelievable powder. They took him out and showed him the Back Bowls. And Pepi looked around and said, “Wow, what a place.” That’s when Bob Parker named the run Wow.

A snowcat was going down, and they asked Pepi to ski down toward the snowcat. And Pepi, of course, a great powder skier, was just dancing down the mountain. He kept going and skied past the snowcat, just yodeling and having the time of his life. They were all waiting for him as he hiked back up to the snowcat, and when he got there, he said, “I could’ve gone forever.” And that’s how the name Forever came about.

As for Pepi’s Face, it used to be called the Austria Face. During a World Cup race [years ago], every one of the Austrians slid down the face because the fire department came up and sprayed water on the course to make it icy.

Pepi: I was everywhere back then—in the Alps, in Chile, in Sun Valley. But I found the best place here.

Other Notable Names

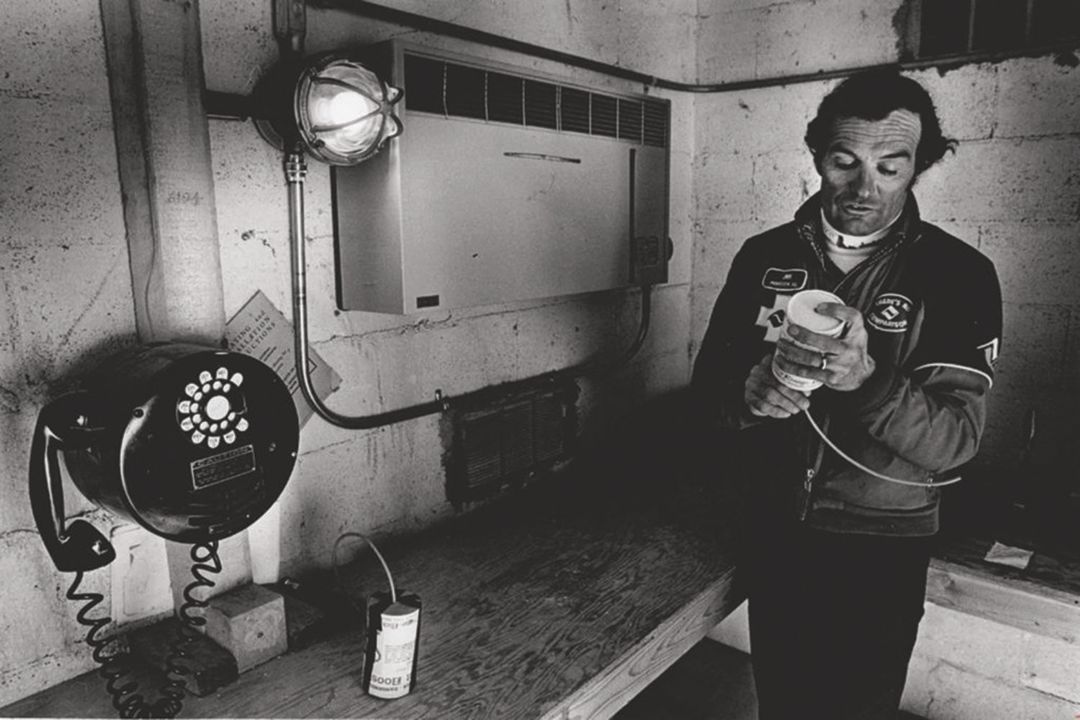

Widge Ferguson, a Vail classic

Image: Courtesy Widge Ferguson

Vail Mountain

In the Wuides: A classic rolling slope in Blue Sky Basin, this was named for former Vail patroller Paul Testwuide (pronounced Test-weed), who played a key role in the resort’s Blue Sky expansion. If you catch it on the right powder day, without a west wind, you can almost close your eyes and float down to Earl’s Express.

Look Ma: Maybe you’ve heard of the naked spread eagle that got pro skier and BASE jumper Shane McConkey banned from Vail. Well, this is the run he did it on—in full view of the Midvail masses.

Milt’s Face: A fast, sustained powder pitch on the skier’s right side of Sun Up Bowl, this run is named for Milt Wiley, assistant ski patrol leader in the early ’60s, who, as the honorific suggests, pretty much owned it.

Northwoods: Now one of the most popular frontside runs at Vail, this trail was cut five years after Vail opened and was the first alley to bisect the tall, regal forest through which it runs. When the Back Bowls are skied out, you can still find soft fluffy snow here.

PPLC: Every mountain has its test pieces, and this is one of Vail’s. The letters stand for Prima, Pronto, Log Chute—a grueling trifecta of big-league bump runs that ends at Chair 10. There’s no finer finale to an epic powder day than skiing this thigh-frying sequence without stopping.

The Skipper: Longtime locals remember the Vail Trail as the resort’s weekly paper of record. This frontside steep is named for the paper’s founder, George Knox Sr., who started it when he was 62.

Widge’s Ridge: In the early ’70s, Bob Parker, one of Vail’s founders, noticed that whenever Widge Ferguson came to town from Denver, it snowed. He named this long run in Sun Down Bowl for her. Widge, a Village resident now in her 90s, stopped skiing a few seasons ago, but she still strolls down Gore Creek Drive to have lunch at Pepi’s or catch an evening show at the Amphitheater. “The thing I liked about it is that it almost always had good snow, and I loved the pitch,” she says of her namesake run. “I suppose it was very hard not to like, because it has my name on it!”

Beaver Creek

President Ford’s: This lappable Beav staple honors the 38th US president, one of the resort’s first investors, who paid $300,000 for one slopeside acre and built a home there after snowcat touring at the resort in 1979. When Ford cut the ribbon on opening day in December 1980, Robert Redford and Jean-Claude Killy were in the crowd.

Rose Bowl: This carpet of snow cascading down the east side of Beaver Creek Mountain was named in honor of Vail executive George Gillett’s wife, Rose.

Trappers Cabin: This on-mountain luxury lodge, which took its name from Trappers Cabin Lake in the Flattops, belies its frontier moniker. Rose Gillett knew the secluded retreat—tucked away in an aspen grove at 9,500 feet—would thrive as a high-end getaway, and rightly so: today, it’s base camp for the resort’s ultra-luxe $50,000 White Glove Package.

Mike Larson on Beaver Creek’s saddle-themed “Cinch”

Image: Ryan Dearth

Mike Larson

The former planning director for Vail Resorts, Larson was a member of Beaver Creek’s naming committee in the late ’70s, along with Don Simonton and Dean Kerkling.

When we started at Beaver Creek, you couldn’t see any lights downvalley. This was the summer of 1975. Vail Associates had purchased the Willis Nottingham Ranch, then added a Forest Service permit above that. The whole idea of Beaver Creek was to push it through fast and have the 1976 Olympic Alpine ski races there. The main spine going out of the village is called Centennial, and the last face is called 1876, in advance of 1976. The Centennial race course was to be the Olympic downhill.

I think losing the Olympics was the best thing that ever happened to Beaver Creek, because they were going to try to build the main area in one year. And it ended up taking us five.

We had a theme for each main lift. Chair 11, there were really good wildflowers up there. So we’d research a list of wildflowers and ideally pick names that reflected the character of the trail. Loco—short for locoweed—is a steep run.

Originally, Spruce Saddle was called Mid Willis, for Willis Nottingham. And everyone hated it. It’s not an evocative name. We changed the name because that saddle has really nice spruce trees. The saddle theme led to trail names like Tack and Leather and Cinch.

I first came up to Vail because I was running a hang glider school down in Denver, and all these guys from Vail ski school and patrol came down to fly. I got a job on patrol, and when I moved over to Beaver Creek, I wanted to fly my glider from the top of the Birds of Prey lift. I’d see all kinds of raptors there, so I named the lift and runs after them.

We had a nesting pair of peregrines on the big cliffs at the bottom, but people wanted to research them, so we kept quiet about them. I saw all the others too: Goshawk, Golden Eagle, Redtail. Kestrels are a small sparrow hawk, and they’re not frequent, but yes, they’re up there.

Royal Elk Glade came from spotting royal elk up there—bulls with a six-by-six rack, minimum. It was a really good hunting spot. All the Gore Range names off Chair 5—(Mount) Powell, Piney (Lake), Red Buffalo (Pass)—are visible from their respective trails. And there’s also stuff like Strawberry Park, which was named for its wild strawberries, and Willy’s Face, after famous German ski coach and Vail resident Willy Schaeffler.

Bachelor Gulch took its name from the group of old bachelors who lived there during the lettuce-farming and sheep-ranching days. Their cabins were all still around when I started working there. I remember going in and thinking someone could be living here.

Arrowhead relates to the Utes. We came upon seasonally occupied Ute summer camps all through the valley. We used to find arrowheads like crazy. There was a sheep pen, and there are still big rocks where they had their fireplaces. It was a perfect location: they could see up and down the valley, had great weather, great water, but no one could see them.

Sandy Treat

Image: Ryan Dearth

Sandy Treat

A 10th Mountain Division vet and 30-year Vail Valley resident, Treat still gives a weekly fireside chat/history lecture on Friday afternoons at the Colorado Ski and Snowboard Museum—at age 95.

I skied at Vail for decades before I finally retired here when I was 65. I chose to come here. I could have gone anyplace. I did it first because of my love for skiing, and also for my son.

Names like Riva Ridge and Avanti are part of this area’s history. We were a bunch of 18-year-old kids in the 10th, but we learned well. The division saw a tremendous amount of fighting. Mountain warfare is not like fighting in the desert, a big space. Fighting in the mountains is very confined, and consequently very violent. The 10th suffered terrible casualties in a very short time. A lot of really good fellas didn’t come back.

I think Riva Ridge at Vail is a heck of a ridge to ski. I always have mixed emotions going down it, obviously. Those names are more important to somebody who’s been around them and seen them happen. Riva Ridge was one of the first places the division went when we arrived in Italy.

Avanti, which means “let’s go” and also comes from the 10th, is a run I like to ski when there’s not too many people around. I like to let ’er rip.

Jim Himmes

Image: Getty Images

Jim Himmes

A patrolman at Vail for 25 years, Himmes was on the crew that led Vail’s expansion into China Bowl in 1988.

I worked on ski patrol from early 1970 through 1994. Sun Up and Sun Down bowls were the major draw when Vail opened, and they were so empty you could get two or three powder days out of each storm.

When we first skied China Bowl, it was closed to the public. We used to call it “out-of-the-area familiarization,” just in case we had to go rescue someone out there. But it was also our playground. Here was all this untracked powder, just waiting to be skied.

The Chinese theme came from the rock wall next to Chair 21. Someone thought it looked like the Great Wall of China, so they called it “China Wall” and everything else followed suit.

Around 1985, myself and another patrolman were in charge of avalanche control back there, and we ran the China Bowl Snowcat Tours. People would pay good money to come over and ski untracked powder in China Bowl, because it was still closed. To help establish where we were in case we needed help, we picked a bunch of Chinese names and named everything. The major runs now are Genghis Khan, Bamboo Chute, Jade Glade, and Chopstix.

After running the snowcat tours for three years, they finally put in Chair 21 and opened it to the public. And that was a big deal. They used a gong and everything.

Henry, Vail Mountain’s first avalanche dog

Image: Ryan Dearth

Henry

Vail Ski Patrol supervisor Chris “Mongo” Reeder adopted Henry in Michigan during a cross-country road trip; the golden retriever debuted as Vail’s first avalanche dog in 2007 and retired in 2017.

We have four avy dogs including Henry on patrol now.

Henry was the perfect dog to start our program with. Even when he was a puppy, he’s always been super mellow and had a lot of drive. Some dogs are into other dogs or have stick-and-ball disease; Henry has always been into people.

There are two methods to train [avy] dogs. One uses treats, and we use a game of tug-of-war. The only time we play the game with them is when they find a victim under the snow. We’ll dig a snow cave and someone will climb in for training purposes. When the dogs find them, the person in the snow cave is trained to give them that toy and play tug-of-war with them like it’s the best game in the world.

All four of our dogs get paid: their food is covered and their medical bills are covered. They become quasi celebrities: Henry even has an avalanche path named after him in Blue Sky Basin, in the trees between Steep & Deep and Lover’s Leap.

Henry still comes to work with me every other day. When he was younger, his strength was how fast and hard to trick he was. Now, in retirement, I think what he’s good at is the PR side of it. His favorite thing to do is lie in the snow in front of Patrol Headquarters, right next to Henry’s Hut, the warming hut named after him. There’s just a mob of people surrounding him all day long, loving on him.

I couldn’t imagine a better life for a dog than being an avy dog—especially Henry. He’s part of our history and culture.