The Last Fugitive: Vail's Connection to America's Most Wanted Eco-Terrorist

October 1998 was a busy time in Vail. The valley was preparing to host the World Alpine Ski Championships in a few months, and a long-in-the-works expansion into Blue Sky Basin, on the south side of Vail Mountain, finally had been given a green light by the US Forest Service. To create ski runs in Blue Sky, the resort was planning to clear more than 800 acres of old-growth forest where lynx and elk lived. Environmental groups including the Sierra Club and Colorado Wild had fought the expansion in court for years. That summer, a series of protests tried to stall the work again, to no avail. Logging was slated to begin on October 19, a Monday.

At 3:30 that morning, a fire alarm went off at Vail’s Ski Patrol Headquarters (PHQ). Twenty-four minutes later, an alarm sounded at Camp 1, a mile east. Four minutes after that, at 3:58 a.m., an alarm activated at Two Elk Lodge. A trio of hunters had been camping at the top of the mountain that night, and when they woke up to crackling outside their tent, they found PHQ engulfed in flames—and the entire sky aglow. They called 911 at 4:10 a.m.

Before long, word reached Mike McWilliam at his home in Edwards: much of Vail Mountain was on fire. He could see the orange glow from his driveway. As the detective on duty with the Eagle County Sheriff’s Office (ECSO), McWilliam knew almost immediately that the fire was not the work of nature: “You can’t have eight different structures on fire spread out over a mile and not have arson.”

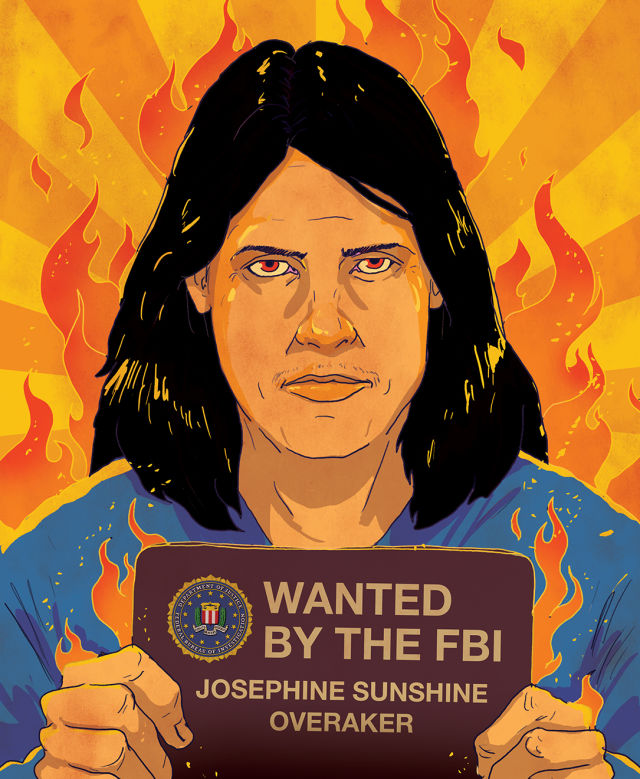

Although only two people were charged with actually committing the act, the FBI determined that five others had helped plan and orchestrate it, including a 23-year-old herbalist and wildland firefighter named Josephine Sunshine Overaker. Eventually, six of those seven would be caught and arrested. The mastermind, William “Avalon” Rodgers—who’d selected Vail as a target, conducted reconnaissance, and ultimately had run more than a mile of alpine ridgeline in the dark, igniting buildings as he went—was snared as part of a nationwide bust on December 7, 2005, that the FBI dubbed the Takedown. It marked the beginning of the end for the Family, a tight-lipped cell of environmental and animal extremists responsible for more than 40 criminal acts over six years, including the Vail arson, which resulted in $24.5 million in damage.

When the Takedown unfolded, however, Overaker was nowhere to be found. She was one of the Family’s most prolific members, having participated in eight arsons in three years, but she’d disappeared more than a year earlier. “In retrospect, I guess we should’ve been paying more attention to where she was,” says retired FBI agent Jane Quimby, who led the Vail investigation from Denver. “But I remember there was not this sense of urgency, like, ‘Oh my God, we’ve got to find Sunshine, because if we don’t we’ll never see her again!’ She was kind of a vagabond. She didn’t have a lot of money. We all thought, here’s this hippie chick, kind of a free spirit, she’s not going to go deep underground. She’s going to surface.”

Yet more than 20 years later, Overaker remains at large. And today, of the 18 suspects who were indicted for the Family’s crimes and the 7 who were charged with the arson of Vail, Overaker is the only fugitive.

Burning Vail Mountain became the Family’s signature act, but it followed a long run of smaller-scale precedents in the Pacific Northwest, according to court documents detailing their spree and interviews with active and retired law-enforcement officers. By the time the septet drove to Eagle County in three vehicles in early October 1998, the record shows, they were prolific arsonists and revered in some activist circles, even if no one knew their identities. They’d burned federal buildings in Oregon and Washington, claiming responsibility under the banners of the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and Animal Liberation Front (ALF), two UK-based organizations that acted in defense of natural entities. (Despite those claims, according to FBI agent Tim Suttles, who has worked the case since 2006, the Family’s alignment with ELF stemmed solely from seeing someone wearing an ELF T-shirt at a festival and deciding their missions overlapped.)

Image: Michael Byers

Overaker and her then-boyfriend, Jacob Ferguson—who would go on to become one of the most notorious government informants in modern FBI history—were living in Eugene, Oregon, in October 1996 when they started the Family’s first fire. They tried to burn down the US Forest Service’s Detroit Ranger Station about 100 miles northeast of Eugene. Their ignition system malfunctioned, but they torched a truck and spray-painted “Earth Liberation Front” and “Stop Raping Our Forests U.S.F.S.” on a building. Two days later, they upped the ante, this time with the help of Kevin “Dog” Tubbs, an animal activist who had worked at PETA and as an editor at Earth First! Journal. Authorities say Overaker and Ferguson used timers to ignite a 25,000-square-foot federal research station in Oakridge, Oregon, destroying the structure and causing $5 million in damage.

Overaker participated in three more arsons over the next two years before agreeing to help with Vail. She and other ELF “elves,” as they called themselves, were meticulous when it came to covering their tracks. They never talked about their plans indoors in case a building was bugged, avoided ATM and traffic cameras while driving to and from their crime scenes, wore socks over their shoes to prevent traceable footprints, and changed their vehicle tires after an arson, discarding the old treads in multiple locations. Everyone used at least one nickname to help protect them if a cell member got arrested, but Overaker, who stood 5-foot-3 with a large tattoo of a bird across her upper back, had the most: She went by Lisa Rachelle Quintana, Maria (her preferred moniker among the Family), Osha, Jo, China, Josie, and Mo. She was known to abuse heroin and other drugs.

Rodgers, as close to a ringleader as the Family had, wanted to do something big before the Blue Sky expansion. He didn’t tell the other members what their target would be until they got to Colorado. Overaker helped cache about 75 gallons of fuel halfway up Vail Mountain, where the cans would be transported higher and transferred into smaller jugs by Rodgers. It didn’t matter that Overaker left Vail and drove home to Oregon a week before the arson with four of her friends, unsure whether Rodgers’s plan would work. In the government’s view, she’d committed domestic terrorism by staging the fuel.

Two days after Rodgers ran the ridgeline, a communiqué sent from a Denver library by Chelsea Gerlach, the only cell member who’d stayed with Rodgers, claimed responsibility. It read:

ATTN: News Director

On behalf of the lynx, five buildings and four ski lifts at Vail were reduced to ashes on the night of Sunday,

October 18th. Vail, Inc. is already the largest ski operation in North America and now wants to expand even further. The 12 miles of roads and 885 acres of clearcuts will ruin the last, best lynx habitat in the state. Putting profits before Colorado’s wildlife will not be tolerated. This action is just a warning. We will be back if this greedy corporation continues to trespass into wild and unroaded areas. For your safety and convenience, we strongly advise skiers to choose other destinations until Vail cancels its inexcusable plans for expansion.

---Earth Liberation Front ( E.L.F.)

The message was sent from an anonymous account, which underscored the bottom line for the elves: If no one talked, they’d never get caught.

It didn’t take long for a massive investigation to take shape. ECSO Detective McWilliam, overwhelmed by the scope of the case, called in the ATF and the FBI. They set up a command post at the main fire station in Vail, later moving to the Christie Lodge in Avon. Five agencies—the Forest Service and Vail Police Department were involved as well—began profiling all sorts of potential culprits, from disgruntled Vail Resorts employees to Earth defenders. The initial theory was that the arson was the work of three to five “non-locals with local assistance,” says Jane Quimby, the retired FBI agent. Protesters from the prior summer were summoned to testify in front of a grand jury; one refused to do so on multiple occasions, even when threatened with jail time. The ATF planted an agent undercover, but the agent got exposed.

Due to the lack of witnesses and forensic evidence, the case went cold fast. Quimby inherited it in late 2000. A Grand Junction native and former all-American guard at the University of Utah, Quimby had spent much of her career specializing in Mexican drug cartels before she began leafing through the file and noticing gaps in the investigation—tips or potential leads that no one had followed up on. “I can remember going to my supervisor with the file, and I’d marked dozens of things with little colored sticky tabs,” Quimby says. “And he says, ‘What is that?’ And I say, ‘These are things that we didn’t do.’”

A few months before Quimby took over the investigation, two hunters discovered a number of red plastic, 5-gallon gas cans stashed high on Vail Mountain under downed trees. The FBI traced their bar codes and learned they’d been purchased from a hardware store in Glenwood Springs in the fall of 1998—a fact that would prove crucial to the prosecution later.

In early 2001, Quimby and her counterparts from across the country convened a meeting in Denver to discuss the case. By then, John Ferreira, a veteran agent based in Eugene who’d been investigating the arsons since 1996, had developed a theory. It centered on Overaker, who’d made the first of two critical mistakes when she left an address book in a payphone booth en route to burn the Detroit Ranger Station with Ferguson. She was later arrested for shoplifting a flashlight and sponges (which the group often used to start fires) on her way to an arson in June 1998 in Tacoma, Washington. The book and arrest didn’t implicate Overaker outright, but Ferreira had been shaking the trees in Eugene and grew suspicious of her. “Some of the investigators thought she might’ve been a goofball making these dumb mistakes, so I think she was in some way seen as a liability, because of these errors that were so crucial to our investigation,” says special agent Ted Halla, who investigated the arsons in Washington state.

Image: Michael Byers

At the summit in Denver, every agent had a theory. Ferreira made his case that Overaker should be considered a prime suspect in the Vail arson. “This is the girl,” he said. “It’s going to be this girl.” Quimby disagreed, believing it had to have been the protesters; they were already on the mountain and had both motive and opportunity. But Ferreira, who died of a heart attack in 2018, was insistent. “John’s like, ‘I’m telling you about this girl Sunshine,’ and he’s going through all of her history,” Quimby recalls. “He’s like, ‘She’s just the type who would do this. It’s her, it’s her, it’s her.’ I can remember my analyst and I walked out, like, he’s just blowing smoke. He’s trying to make her bigger than she is. He was so passionate and enthusiastic, but we thought he was full of shit.”

Either way, the agents made a critical change in strategy after that meeting. Instead of tiptoeing around covertly, they came up with a list of 30 to 40 suspects and potential associates and decided to contact every one in person—a shift spurred by an activist who’d told them there was “nothing more powerful in terms of scaring the shit out of us than when the FBI knocks on our door.” As Quimby puts it, “We started a very aggressive campaign from then on, telling everybody: We are coming after you.”

Over the next few years, Ferreira focused on Ferguson, Overaker’s former live-in boyfriend and a known heroin addict whom the agent believed was the most likely conspirator to “flip” and become an informant. (Ferguson had a young child, thus ample incentive to stay out of prison.) Ferreira finally convinced Ferguson to play ball nearly six years after the Vail arson. In exchange for immunity and $50,000, Ferguson told Ferreira everything he knew—and agreed to wear a wire to implicate his friends. Ferreira called Quimby. “I got this guy,” he said, “and he told us who did Vail.” Quimby flew to Oregon and met with Ferguson. “He started naming names of all these people,” Quimby recalls—including Overaker. “There was no remorse. It’s kind of like an artist claiming credit for what he had done. He wasn’t bragging about it, but he wasn’t sorry it happened.” From then on, the FBI called its investigation Operation Backfire.

After Ferguson, the Family’s most prolific arsonist, agreed to cooperate, the agents took him on a tour of the West to corroborate the Vail details, like where the gas cans were purchased in Glenwood and where the group camped (often at rest stops). Ferguson also secretly recorded eight former accomplices talking about their crimes. Those accomplices did not include Overaker, but they did include Rodgers, who committed suicide in his jail cell two weeks after his capture, much to law enforcement’s dismay.

The arrests and indictments were announced six weeks after the Takedown at a press conference in Washington, DC, attended by, among others, then FBI Director Robert Mueller. Overaker was indicted but had likely left the country by then.

Due to the cloak of secrecy that members of the Family adhered to, even those who knew Overaker didn’t know much. She grew up in California, according to FBI agent Suttles. Beyond that, Suttles declined to expound. None of the long feature stories about the Family in Rolling Stone or Outside or Maclean’s revealed much about Overaker’s background. Still, convicted cell member Darren Thurston did tell a Maclean’s reporter, based on Thurston’s access to discovery during his trial, that the FBI had spoken with Overaker’s family and former friends through contacts retrieved from the address book she left behind 10 days before the Detroit arson. Suttles wouldn’t comment on those conversations. My attempts to contact a handful of Overaker’s co-conspirators and friends, either directly or through intermediaries, resulted in no reply or a decline to comment. Most, it seems, had completed their prison sentences and moved on with their lives. Tubbs was the only convicted Family member still on probation, but he wasn’t interested in talking, either.

To be clear, Overaker was no mastermind. “She was more of a follower, a good follower who also was very committed to the cause,” says Quimby, who retired from the FBI in 2010. “I just think we underestimated her a little.”

Authorities believe Overaker took part in two more actions after Vail, including a final arson in Oregon on Christmas Day 1999. Then she simply disappeared. The cell committed its final crime in October 2001 (by then, the group’s tactics had evolved to include night-vision scopes and model rocket igniters, and Rodgers and Stan Meyerhoff were considering assassinations as a way to amplify their message). A warrant for Overaker’s arrest, on a charge of identity theft, was issued May 6, 2004, after she obtained official identification from the state of Oregon under an alias. “She had been looked for, but we couldn’t find her,” Suttles says. “So the feeling was that she likely left the country.”

Perhaps Overaker knew a day of reckoning was inevitable and chose to cut ties before it arrived. Maybe she wanted out of the activist bubble that the Pacific Northwest had become.

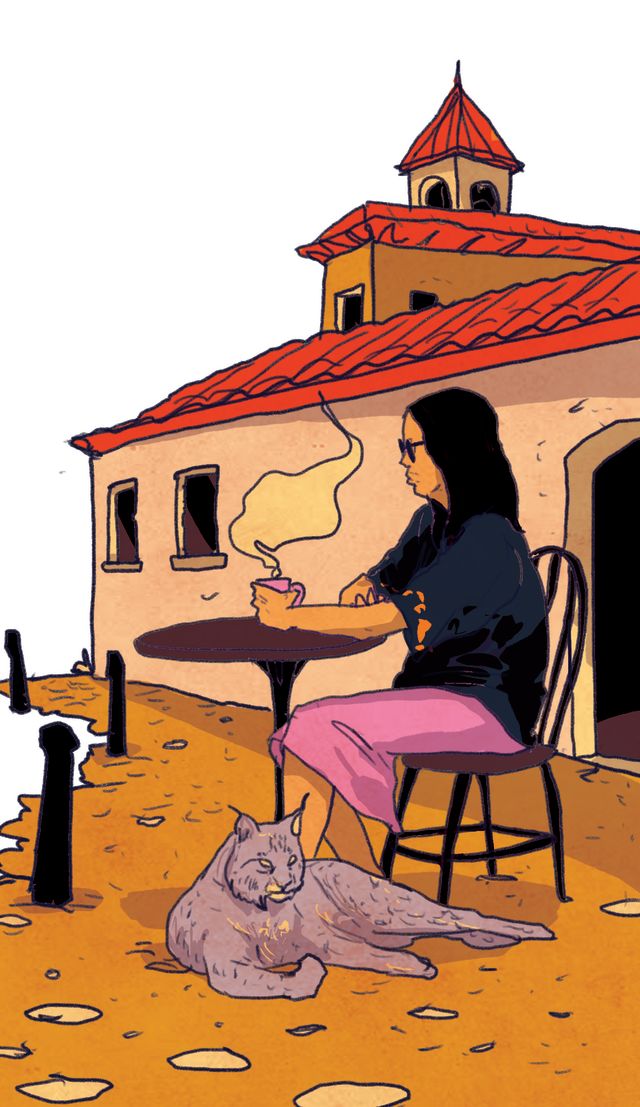

A month after Rodgers’s suicide, 28 beagles were stolen from a veterinary lab in Madrid, Spain. ALF claimed responsibility and dedicated the action to Rodgers. Given that Overaker was fluent in Spanish and thought highly of Avalon, Suttles thinks she may have taken part in that crime and begun a new life overseas.

The Family is still a polarizing group in the activist community, even if some members later admitted their actions did not accomplish what they’d hoped (torched buildings were rebuilt with insurance money, released animals were recaptured, and friends helped send friends to prison). “I’m not sure what burning down a restaurant does to help the lynx, because they had to rebuild it with huge logs,” says McWilliam, now Eagle County’s Undersheriff. While informants like Ferguson and Meyerhoff were castigated online, Overaker became a hero to some—and forgotten to others.

The movement evolved away from violence, but bitter feelings remain. A spokesperson I contacted at the Earth First! Journal, still a leading voice among activists, wouldn’t agree to be interviewed about how today’s tactics compare with those of the Family unless I promised not to name Overaker in my story.

“We aren’t interested in participating in the further exposure of someone the FBI is currently seeking, or in disparaging anyone’s actions in defense of the earth,” he wrote in an email. The long prison sentences and high-profile busts likely served to dissuade future violence and destruction among like-minded activists. But it’s still a fraught space. Vancouver, BC’s popular Sea to Sky Gondola was sabotaged last summer in a crime that remained unsolved at press time. There is still plenty of opposition to logging.

“You definitely don’t need to burn down a building to make your point,” Greenpeace Media Director Travis Nichols told me. He added in an email: “As politics turn uglier, more militant, more divisive, and more hateful, we feel it’s time to reaffirm the values of nonviolence and their importance to lasting social change.”

Image: Michael Byers

Overaker, who turned 45 in November, faces 19 felony charges and five years (the mandatory minimum for burning a federal building) to life in prison. The FBI believes she could be working as a firefighter, midwife, masseuse, or sheep tender, though that information is likely outdated now. By the time the FBI started interviewing her alleged co-conspirators in 2005, they told agents Overaker had stopped communicating with them. Overaker still has a $50,000 reward hanging over her head, so the tips keep streaming in, about two or three per month, Suttles says. He might send an attaché to investigate if one sounds promising, but that hasn’t happened for years.

“I certainly want to get her,” Suttles says. “It’s kind of ironic that she was the first one wanted, and she is also the last one wanted.”

“Sunshine is the only loose end,” Quimby adds. “I figure she’s either going to end up dead of an overdose or somebody’s going to turn her in or she’s going to give up and say ‘I want to come back to the States.’ But it’s one of those things where, over the course of 20 years, that should’ve happened by now.”

In August 2018, the only other fugitive from the Family, Joseph Mahmoud Dibee, was captured 13 years after he fled the country. US authorities learned Dibee was traveling through Cuba en route to Russia, and Cuban officials detained him before he boarded his plane.

Overaker, too, could be traveling internationally, though that’s unlikely. Sometime after the Takedown, FBI agents learned Overaker had stolen a passport and possibly had used it to travel to Spain. Suttles says the passport would trigger a law-enforcement response if presented to a customs official. But he declined to say whose name it contained, “just in case she’s still using it.”