Railroad Row

It’s early April in Eagle County’s most famous railroad town, and Earle Bidez is resurrecting Minturn’s past.

Over there by the river is where the roundhouse used to stand, until a locomotive famously broke through its wall in 1913, coming to rest just shy of the large cottonwood. On the north end of the railyard, you can see the low-hung brick depot building. Bidez, the two-term mayor and a Minturn resident of 42 years, has just finished lunch at the Mexican Bar and Grill (address: 160 Railroad Ave), which recently opened south of the depot in the old Turntable Restaurant building. Bidez took his first job there in 1981, a Georgia boy who arrived in a suit because he’d never been to Minturn and thought it must be swanky, close as it was to Vail. He worked as a line cook on the graveyard shift—10 p.m. to 6 a.m. He went on to buy a house with a garage built of stacked railroad ties.

“The railroad is in our DNA,” Bidez says, pointing out that the town was named after a Denver railroad executive, Robert Minturn Jr. “But quite frankly, after it was abandoned in the ’90s and the town has gone without it, I think a large majority of the community is not in favor of reactivating it.”

There’s a reason why it’s even a topic of conversation—a number of reasons, actually. With workforce housing deemed a top priority, and congestion on roads increasing from Vail Village to Dotsero with every new development that gets greenlighted, local government planners and leaders have quietly weighed the merits and costs of a railroad revival in Eagle County. Meanwhile, as the volume of railroad freight continues to surge in the wake of pandemic supply chain bottlenecks and the war in Ukraine spurs calls for an increase in domestic oil production, litigation and environmental analyses playing out thousands of miles away could impact whether trains return.

Colorado is the likely throughway for billions of gallons of so-called “waxy crude” being transported from Utah’s Uinta Basin to refineries on the Gulf Coast, via a route that runs along the Colorado River and could, in the future, local leaders fear, travel through the heart of Eagle County and over Tennessee Pass. The same railroad corporation—Texas-based Rio Grande Pacific (RGP)—that is going to move the crude recently leased the Tennessee Pass Line from Union Pacific via a subsidiary and says it is intent on exploring passenger rail in the valley. Yet none of the towns or counties seems willing to pay for the infrastructure that mass transit would require—a total in the realm of nine figures—and RGP has made it clear it’s unwilling to assume the cost alone. All of which has people wondering if the lease is actually a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Minturn, by way of its history and cultural evolution since the trains stopped running in 1997, is reluctantly cast as ground zero for the broader debate. There were 1,080 residents in town when Bidez moved there, and Eagle County had 14,000. The county’s population has quadrupled since then, to 55,000, but Minturn’s has decreased, to 1,038. “That’s because people don’t want it to change,” Bidez says. “It’s the most beautiful valley, I think, in the county. And we’ve always wanted to maintain our small-town heritage.”

Has the town evolved too far from its railroad roots to return? Has the Vail Valley? As much as the question is logistical, it’s also cultural, Bidez says. “There has been a changeover of demographics, and the people who live in Minturn are very possessive of their town. Yes, the railroad and mining are our history and we’re very proud of it. But celebrating that history is something we can do while also saying we’re not going to support the railroad coming through.”

A passenger train departs Tennessee Pass station, south of Camp Hale, in 1922.

Train travel through Minturn dates to 1881, when the line over 10,424-foot Tennessee Pass—2,600 feet higher than Minturn—was completed. The town would not be incorporated for another 23 years. The railroad primarily carried freight, in particular coal, from Grand Junction to Pueblo. But it also ferried passengers between towns, a crucial option at a time when automobile reliability and road quality were nowhere near today’s standards. The line ran until 1997, when Union Pacific mothballed its tracks shortly after a pair of crashes on the Minturn side of the pass attracted national attention.

The first occurred early on the morning of November 22, 1994. A train carrying ore from Wisconsin to Utah derailed at 60 mph, losing 51 cars piled high with taconite. The conductor leaped to safety just before the wreck, breaking his leg. Sixteen months later, on February 21, 1996, a hazmat load traveling from Illinois to California jumped the tracks after two feet of snow had fallen, killing the engineer and an apprentice. The crash spilled 70,000 gallons of sulfuric acid across Highway 24, requiring a massive cleanup.

Longtime locals no doubt will recall those incidents as they consider that the Uinta Basin railroad could send up to 10, two-mile-long heated oil trains through Colorado each day. Along with several environmental groups, Eagle County sued to overturn a 2021 Surface Transportation Board approval (the US Forest Service gave it a green light too) of a new 88-mile railroad in Utah that enables Uinta Basin wells to quintuple production and fast-track their sludge to Gulf Coast refineries. That claim is pending. In March, US Senator Michael Bennet and Representative Joe Neguse sent USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack a letter calling it “beyond reckless” to expose the Centennial State to the inherent hazards of transporting waxy crude from Utah. Among many considerations, the Colorado congressmen cited “the recent train derailment and environmental disaster in East Palestine, Ohio, which has laid bare the threat of moving hazardous materials by rail.” To their point, if Colorado is to expect an oil spill every four years, as federal analysts have predicted with Uinta’s crude route, what will that look like?

The Tennessee Pass Line represents something of a wild card. Owned by Union Pacific and long coveted for its freight advantages and mass-transit potential—despite being twice as steep as a normal grade—it is seen as the only viable alternative to transporting crude through Colorado if the Moffat Tunnel were to be compromised or exceed capacity. RGP secured a lease for the line in December 2020, and soon after, its subsidiary, Colorado Midland & Pacific (CMP), contacted towns and counties about the potential for passenger rail, to take vehicles off I-70 and Highway 24. Eagle County and the Town of Minturn weren’t interested in reviving the line, ending the conversation. “The cost was enough that nobody could put a lot of hope into the rails becoming active again,” Eagle County Manager Jeff Shroll says. Bidez adds: “We wouldn’t pay a dime for that.”

Minturn residents pose with Locomotive No. 513 after it crashed through the wall of the Denver & Rio Grande roundhouse in 1913

The lease, terms of which CMP spokesperson Sara Cassidy wouldn’t disclose, includes 160 miles of track starting near the Eagle County Regional Airport in Gypsum and ending in Parkdale, near Cañon City. “We aren’t selling something. We aren’t trying to push something,” Cassidy says. “We’re just trying to offer the idea that the rail is available. We don’t intend to pursue passenger operations on our own.” As for the possibility that RGP would someday use the line to transport waxy crude, the company made a court filing in March 2021 promising to exclude hazmat loads from its cars if it comes back.

Just before this issue went to press, KCVN, a New York-based firm that in 2022 had purchased a bankrupt railway in Colorado’s San Luis Valley and had hoped to haul grain and possibly passengers over Tennessee Pass announced that it was abandoning a competitive bid to revive the line. All recent signals from RGP suggest there is little urgency to press towns and counties for mass-transit funding. So what does that say about the end goal—and the railroad’s promise not to amend its filing in the future? Could Rio Grande never transport oil over Tennessee Pass, or just not initially?

“That’s like saying if you buy a house, could you change your mind and sell it later? Of course,” Cassidy says. “But I’m not going to speculate on that.”

Exactly how much control the community holds over its railroad future remains to be seen. It’s not as simple as stiff-arming waxy crude and moving on. Before taking the county manager job five years ago, Shroll spent a quarter century as Gypsum’s town manager. Adding passenger rail service to the valley “has always been a dream,” he says, and something he included in master plans as early as the ’90s. “I used to ask, how come you can’t take an old, dilapidated school bus, put in a new engine, modify it to run on the tracks, and send it up and down between here and Minturn?”

Shroll also used to live 40 feet from the tracks, and if the 2 a.m. coal train to Pueblo was late, he’d sit up in his single-wide mobile home wondering where it was. “Back then I was fine with it,” he says. “But I just look at the corridor now and how much we’ve grown. We were a county of just under 30,000 [in 1997] and now we’re up to 55,000. And we’ve built most of that within earshot of those tracks. At the various crossings in the county, there’s a lot more traffic. Look at the Westin. If you’re staying in the rooms that face Avon, I don’t think that’s a bad view. But you run the midnight train I was telling you about under their windows? That could be quite a different experience.” He sighs. “I’m sort of resolved that passenger rail is unlikely to happen in my lifetime. I don’t know how you’d make money by charging five or seven bucks to go up and down valley.”

Ella Burnett remembers when that was the case. Burnett, 96, grew up in Red Cliff and has lived in Minturn since 1948. She rode the train back and forth like a subway throughout her youth. “I really miss the trains, and I would love to see them come back,” she says, with more than a hint of sentimentality. “I just miss the sound of ’em.”

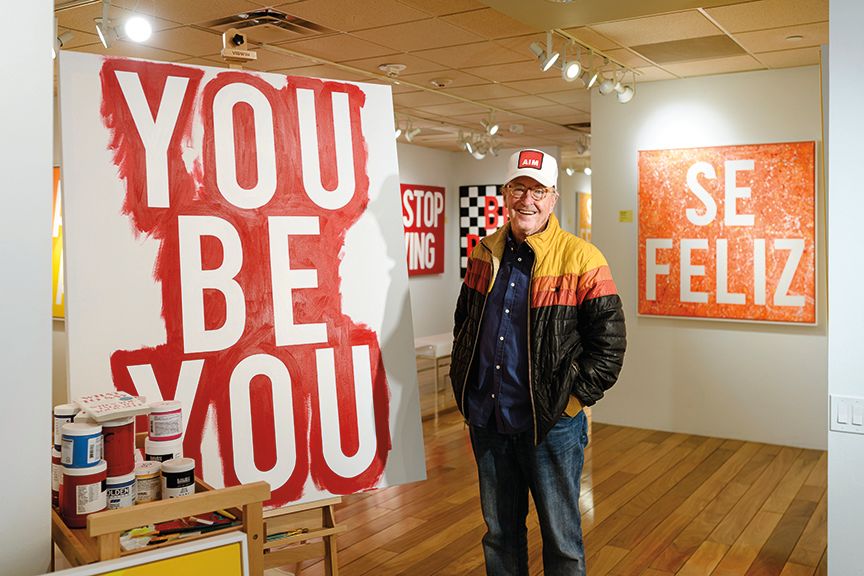

Minturn Mayor Earle Bidez

Image: Ryan Dearth

Others say the opposite. Darell Wegert, who moved to Minturn in 1976 and served four terms as mayor in the ’80s and ’90s, remembers the five-minute-long squeeeeeeeeeak when a train arrived, as well as fielding complaints from residents about the noise of diesel trains idling all night next to homes instead of farther north in the railyard. “We would talk to them, but they wouldn’t do anything,” he says. “Dealing with the railroad was very hard. A lot of times they would totally ignore us.”

Still, at 73, Wegert is a self-described “railroad nut.” He built a large model train in his garden and a smaller one in his garage. He gets together with friends in the valley to talk railroading on a regular basis. But when it comes to the future of trains in Minturn, he thinks that time has passed. “We’ve moved on,” he says. “We enjoy the history of it, we like to make it sound very nice and appraise it, but it’s over now. And I don’t think the communities would receive much financial benefit from any of them.”

Bidez, who is 68 and recently retired, sits on the newly formed Regional Transportation Authority’s board of directors. In a vacuum, he would love to see a passenger rail line between Leadville and Minturn, so long as it was “reasonably fast.” (Leadville Mayor Greg Labbe, Red Cliff Mayor Duke Gerber, and Vail Mayor Kim Langmaid have expressed similar sentiments). Every morning and afternoon, his tiny town deals with what he calls the “Leadville 500—our rush hour.” But he believes the valley is better off pursuing a more robust network of electric buses and using the rail corridor for pedestrian travel (the line was identified by Governor Hickenlooper in 2016 as a rails-to-trails priority).

A vintage picture postcard from the early 1900s.

“Our major concern is they’re trying to make money on this line,” Bidez says of the railroad. “If they spend enough to repair this line, which is going to be really expensive, what’s to keep them from eventually saying oil too can pass through here? We certainly don’t have any control over that, and it’s not clear what the relationship between Midland and Union Pacific might be. But it would be absolutely the worst thing we could ever do. To have that kind of oil freighted through Minturn is anathema to who we are as a citizenship and town.”

Nine years ago, the southern half of iconic Lionshead Rock on the east side of town calved off and rolled down the mountain, obliterating the railroad tracks below. “That kind of damage is going to be all over the place, going up to Tennessee Pass,” Bidez says. The question, then, is what will those tracks look like in, say, a decade?

Only time—and the federal government, a federal judge, a Texas railroad corporation, a Utah oil field, and the decree of a growing community perpetually grappling with its future—will tell.