Eagle's New Assisted-Living Facility is a Game-Changer for the Valley's Seniors

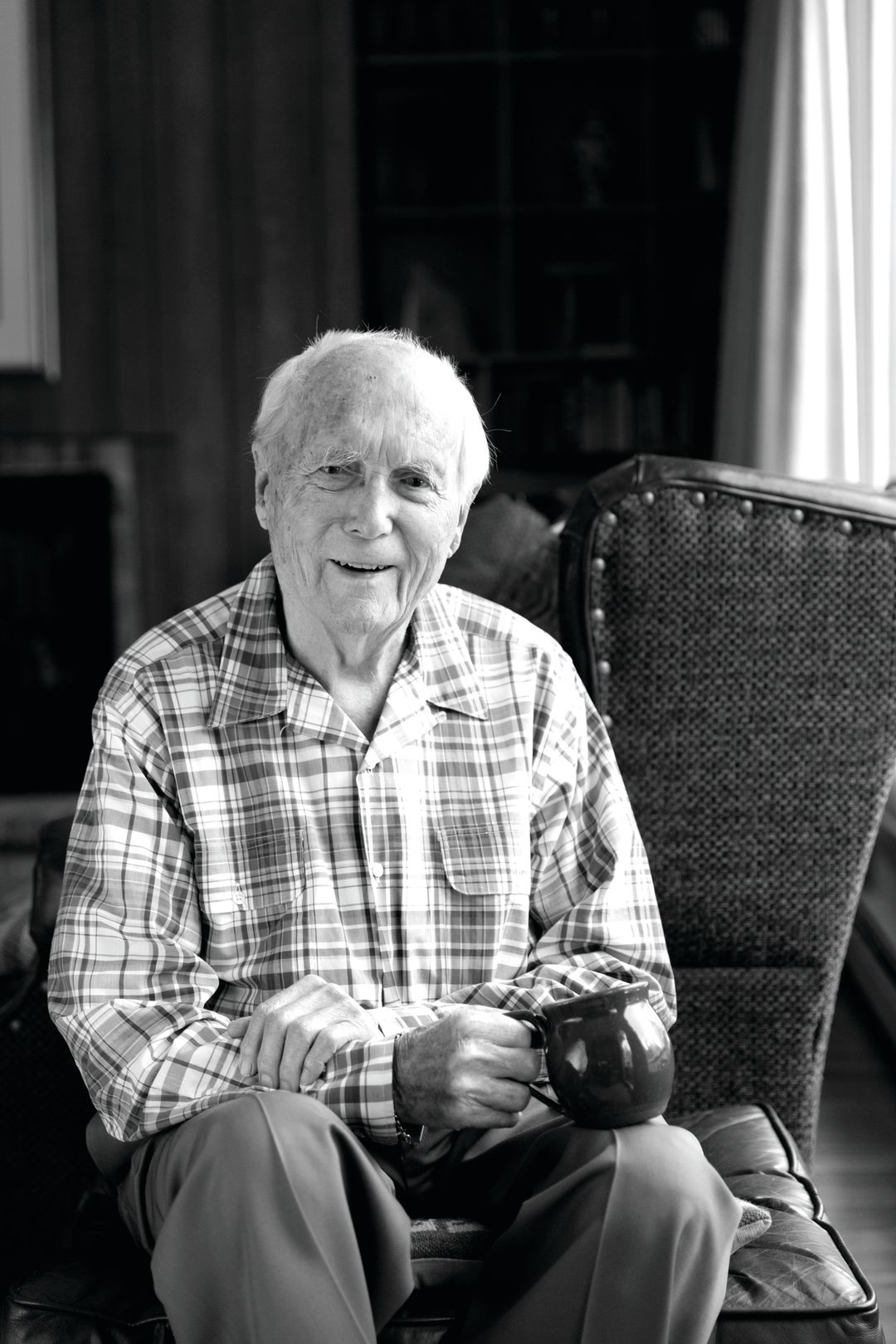

Since he arrived in Vail as the resort’s first full-time physician, Dr. Tom Steinberg has fought to bring assisted senior housing to the valley, a quest now fulfilled.

Image: Rebecca Stumpf

Like many skiers who migrated to this valley in the 1960s, Thomas Steinberg had every reason to believe he would live forever. After all, the Nazis couldn’t kill him, though he had stormed Europe as a G.I. and helped liberate Dachau. But when he moved to Colorado in November 1965, becoming the fledgling Vail ski resort’s first full-time physician, he urged his fellow pioneers to look to the future. In addition to libraries and rec centers and blocks of high-end condos, he said, the town should build what people back then called an “old folks’ home.”

“I kept saying, all you partying young people aren’t always going to be partying and young, so you need to plan for this, or it’s going to be very difficult,” Steinberg recalls.

Now 92 years old and long retired from setting broken bones, Steinberg’s still living with an adult son in Vail. His hair has gone gray, he’s hard of hearing, practically blind, and his voice has gone hoarse—mostly from decades of repeating a mantra that fell largely on deaf ears, he suspects, because of ski country’s celebrated “Peter Pan syndrome,” the collective notion that youthful vigor is a state of mind, and nobody wants to think about getting old.

But time, of course, exacts its inevitable toll. By the 1990s, Eagle County’s over-65 population had more than doubled, then more than doubled again to about 5,500 seniors by 2010. Despite these statistics, by 2015, a half century after the resort’s founding, there still was no home in this valley for elders who wanted to stay, but no longer could live on their own.”

"I kept saying, all you partying young people aren’t always going to be partying and young, so you need to plan for this, or it’s going to be very difficult."

But time, of course, exacts its inevitable toll. By the 1990's, Eagle County's over-65 population had more than doubled, then more than doubled again to about 5,500 seniors by 2010. Despite these statistic, by 2015, a half century after the resort's founding, there still was no home in this valley for elders who wanted to stay, but no longer could live on their own.

This put our county at a decided disadvantage. On average, throughout the country, there are 31 assisted-living units per 1,000 residents over 65. By that measure, a county the size of Eagle ought to have about 150 units of assisted housing for its seniors. Without options, many of the silver-haired pioneers who had founded Vail began relocating to assisted-living facilities in Grand Junction or Denver, and faraway places closer to their families. For want of care, they left behind lifelong friends, homes, businesses they had built from nothing, and nonprofit boards they had served on for decades, creating a vacuum of institutional memory, rending holes in the social fabric of this special place.

“It disrupted the whole community,” Steinberg says. “You lose the experience of those people in the community, that knowledge of what was here and what was done to improve it. And the children that live here were losing their parents.”

Yet in this regard, Vail was hardly unique among ski resort communities.

Dan Shields, who has been in the business of assisted living for 25 years, says that up until a few years ago, assisted living was all but nonexistent in high country. Finally, in this decade, as the need became ever more acute, resort towns began making bold moves.

Three years ago, Shields helped open a senior facility in Steamboat Springs called Casey’s Pond. It’s a gorgeous, 156-unit campus, close to downtown and nature that offers residents every level of care—from independent living through skilled nursing to long-term care. It’s the first of its kind in any rural mountain resort town in the United States, according to Shields.

Doers in Vail, which prides itself as a trendsetter, weren’t far behind. Around the beginning of this decade, the community began to rally around the cause Dr. Steinberg had championed since virtually the day he arrived. In 2013, Eagle County purchased a five-acre parcel of land on the west side of Sylvan Lake Road in the heart of Eagle Ranch and sold a portion for a dollar to Augustana Care, a Minnesota nonprofit that runs two dozen assisted-living centers in Minnesota, Wyoming, and Colorado, including, as

of September, Eagle’s Castle Peak senior care center.

An aerial view of the Castle Peak senior care center taken in early October, just after the first residents moved into the county’s first assisted-living facility.

Image: Rebecca Stumpf

The $25 million facility (the USDA loaned the project $12 million, and the community pitched in to raise nearly $5 million) blends seamlessly with the architecture of Eagle Ranch, looking more like the fitness club across the street than a retirement home. Its 64 units include 20 assisted-living units for people who need help with meals, meds, and getting around; 12 memory care units for people with dementia or Alzheimer’s; 22 long-term care units for people who need more intense nursing services or palliative care; and 10 short-term care units for people of any age who need intensive rehabilitation but are expected to recover, as from a car crash. Monthly rent starts at $5,000 for assisted living, which may seem high, until you consider that $5,038 is the average cost of a monthly Vail Village one-guest home rental on Airbnb, excluding butler, maid, nurse, chef, and three meals a day.

“These types of people shouldn’t have to leave the valley,” says Matt Scherr, marketing director for the center. “Now they don’t have to.”

Castle Peak also creates new possibilities for families who, once isolated from their relatives, can become multi-generational clans.

8.7 percent: The number of Eagle County residents who are over age 65, estimated by the Census Bureau in July 2015

Red Cliff artist Helen Hiebert, for example, has been living in the valley for four years, far from her 78-year-old mother, Doris, who had been living in an assisted-living facility near Oklahoma City near extended family. This fall, Doris relocated to Castle Peak. “To have Grandma around, I think that’ll be nice,” says Hiebert, who as an artist will embark upon an oral history project with her mother, and relishes the opportunity her two teenage kids will have to bond weekly with a grandmother they previously saw only once or twice a year. “It’s a beautiful setting,” says Doris. “And I’m closer to family, which is even more beautiful.”

As groundbreaking as Eagle County’s first assisted-living center may be, it doesn’t begin to meet the valley’s current or projected needs. Those 64 units represent less than half the present national per capita average; by 2020, the county’s over-65 population is expected to surpass 2010 levels by 165 percent.

Still, it’s a start.

At 92, Dr. Tom Steinberg lives with an adult son in Vail, but knows he will have a home at Castle Peak if he ever needs assisted senior care.

Image: Rebecca Stumpf

Other resort towns are taking their cues from Castle Peak. While Summit County may have taken a lead in addressing the affordable housing crisis that also bedevils Eagle County, it has yet to make a dent in assisted living. “We have nothing in Summit County,” says Andy Searls, a former Vail resident who lives in Frisco and is on a committee to bring an assisted-living center to that county. “All these mountain towns really need something, because you have people who’ve lived here almost all their lives, and they don’t want to leave.”

Meanwhile, time marches on. Though it’s notable that there still is no cemetery in the town of Vail—as if death itself has been banished—the dedication of Castle Peak is perhaps one sign that the valley has matured beyond its Neverland pretensions.

Dr. Steinberg, for one, is gratified that he’ll have the option of moving into Castle Peak if and when he needs to. It would be fitting, after all, since one of the units there was dedicated in his name.

“It’s a little bit embarrassing, to have a building named after you,” Steinberg says. “But the center is going to be a blessing for the community, and so I’m glad that it’s finally coming about. And I’m glad I’ll get to see it before I wake up dead.”