Powder Days, Ice Theaters, and Up-Hill Skiers

Image: Charles Engelbert

Snowman: Praying for a powder day? Make that wish care of Larry Hjermstad.

When Vail cofounder Pete Seibert Sr. died in the summer of 2002, his will contained one rather unconventional (but if you knew him, not unexpected) provision: he wanted to be reincarnated as snow.

“Pete’s last wish?” laughs Pete Seibert Jr., a Lionshead real estate broker. “He wanted us to mix his ashes with silver iodide and seed the clouds with him.”

So they gave some of Pete’s ashes to Joe Macy, a local fly-fishing guide and former ski patroller who managed Vail Resorts’ cloud-seeding operations. And Macy naturally called Larry Hjermstad (right), founder and head shaman at Western Weather Consultants, the contractor who has been supercharging altostratus above Vail (and Aspen and Breckenridge and just about every ski resort in Colorado) with downy white fluff every winter since 1976.

“Believe it or not, with all of the ski area work I do, I haven’t had a whole lot of time to ski,” says Hjermstad, a white-haired meteorologist who wears plaid and blue jeans and has advanced degrees in mathematics, physics, and weather modification and atmospheric science. “Plus, I just turned 73, so I need to be a little more careful.”

As for the how-to of cloud seeding, Hjermstad doesn’t launch sounding rockets or fly a biplane. But he does own a mammoth four-wheel-drive pickup truck, which he pilots around the state stocking some seven dozen generators, cloud-seeding machines that look like hot-water heaters topped with fuse boxes that are capped with outsize Bunsen burners. Nearly two dozen of them are tucked behind barns on pastureland upwind from Vail and Beaver Creek.

Hjermstad swears there’s solid science behind the black magic he sells. The theory is simple: each propane-powered generator has a forty-gallon reservoir containing microscopic particles of silver iodide powder dissolved in a solution of highly flammable acetone. When conditions allow—when it’s below freezing and the clouds are low and the prevailing winds are just right—Hjermstad phones his tenders (typically ranchers who are paid $500 to $1,000 a season to operate the generators), who pressurize the tanks and light the burners. The burners, in turn, roar and belch flame that, at 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, oxidizes billions of silver iodide crystals. Convection carries the crystals skyward, and, if Hjermstad has done the math correctly, more than a few will attach themselves to the undersides of clouds. There, they bind with moisture, causing ice crystals to form, which fall to earth as snow.

As to how much snow, well, that’s anybody’s guess, including Hjermstad’s. But based on weather station data and stream flow analysis, he estimates that his machines increase snowfall anywhere between 12 and 35 percent. That means that Hjermstad can personally take credit for up to three feet of the 111 inches of powder that had turned to hardpack on Vail Mountain by the end of January. And don’t blame Hjermstad for January’s drought, either, or for the apocalyptic 2011–12 season. Rather than initiate snowfall, his machines augment it.

Seriously, next time you’re in Durango, look this guy up and take him out for a beer.

Given the negative connotations of “weather modification” (Google Owning the Weather, a controversial documentary in which Hjermstad has a cameo), Vail Resorts doesn’t like to publicly acknowledge the existence of or reveal details about its cloud-seeding activity. And Hjermstad won’t say how much he charges ski companies for his services, but he will allow that it’s a tiny fraction of what each spends on snowmaking operations. But whatever the amount, his bill’s a bargain, given that, by one estimate, every foot of snow that falls translates as $1 million in resort revenue.

Then there’s his freelance work.

When Macy phoned Hjermstad inquiring about the best way to go about fulfilling Pete Seibert’s last wish, he was referred to a cloud-seeding pyrotechnics company in Louisville that mixed the founder’s ashes into silver iodide flares. At dusk on St. Patrick’s Day weekend in 2003, the Seibert family gathered on a ridge atop Bachelor Gulch and watched Macy ignite a line of flares fixed atop bamboo poles. As the fireworks crackled and popped, sending smoke heavenward, the founder’s granddaughter, who was 10 at the time, asked Macy, “Has anybody ever done this before?” To which he replied, “Darling, your grandpa did a lot of things nobody else ever did before, and this is the last one!” Overnight, a foot of new snow fell on Vail Mountain, and Pete Seibert returned to Earth—as a powder day.

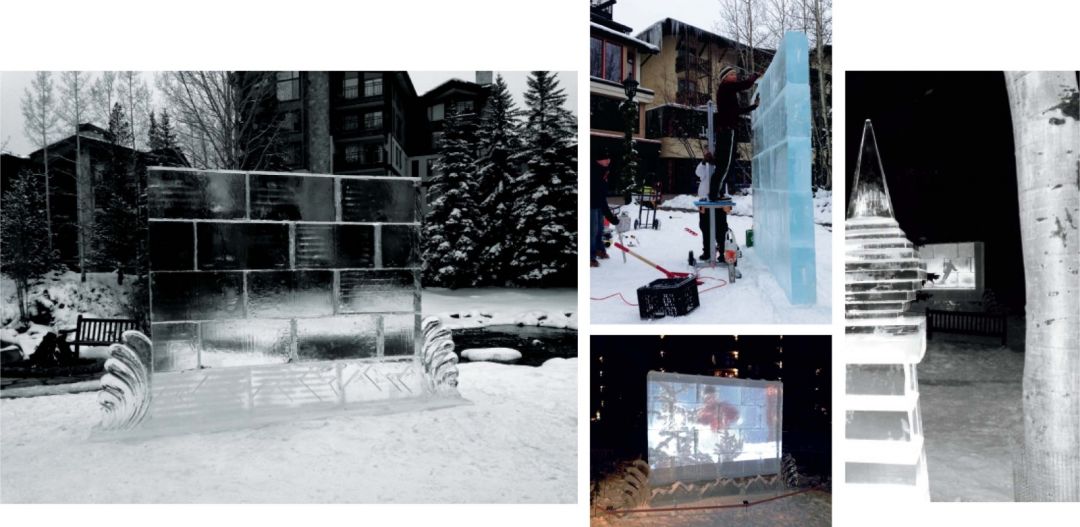

Ice Screen: During Oscars season, the thermostat at Vail’s hottest cineplex tops out at 32 degrees.

For those who see a warm, dark movie theater as the ultimate escape from winter’s cold, be warned: Vail’s newest cinema isn’t going to take the chill out of your bones. Not only is the Logan Ice Theater outdoors, in the brisk heart of Vail Village, but the specific spot, along the Gore Creek Promenade, was chosen precisely for its chilliness and lack of sunlight.

Before you denounce the cinema’s planners as sadists, know this: even though the films shown here are anything but steamy, there’s a real concern that the projection surface might melt.

“It looks like a screen when you go to a drive-in theater, except it’s made of ice,” explains Paul Wertin, the local ice sculptor who chopped, carved, and whittled it.

The Logan Ice Theater, a functional work of art at the heart of this season’s Triumph Winterfest, debuted in mid-December and will be open for screenings nightly, from 5 to 10 p.m., through February—or until the screen itself, ten feet tall and ten inches thick, becomes a puddle of slush. The feature presentation each night is Vail ... Timeless, a specially made, Vail-centric loop of scenes from the Warren Miller archives, dating back to 1962.

The whole project came about as Kent and Vicki Logan, longtime Vail residents and arts supporters, were casting about for a special way to commemorate the resort’s fiftieth anniversary. That occasion was producing a flurry of retrospective films, including documentaries by Vail Resorts and the Vail Ski & Snowboard School (clips of which also show at the Ice Theater). Movies projected onto blocks of ice, an idea hatched by Molly Eppard, coordinator of Vail’s Art in Public Places, seemed ideally inspired.

“What’s more appropriate, in the middle of winter, than a screen made of ice blocks?” Kent Logan says. “Indoors, with a regular movie screen—that wouldn’t be like this.”

Wertin, who worked with special events consultant Nathan Cox of Pink Monkey Solutions to create the theater, finds charm in the project’s quirks. “You can see it’s blocks of ice. You see the seams, the thickness of the wall,” he says. “You get the minor distortions from the ice. It’s a different flavor of ice and light.”

In mid-January, Wertin added a series of backlit ice sculptures, inspired by Japanese lanterns, to enhance the visual drama around the outdoor screen. “It creates this little world out there,” he says, adding that he’d love make that world even bigger in years ahead. “It’s taking ice into a modern art realm.” Among the satisfied moviegoers have been diners at Gore Creek restaurants, who, seated at the right table in a luxuriously heated room, can sneak a peek at the Logan Ice Theater like kids peering over the drive-in fence. On the à la carte menu: Milk Duds and popcorn.

Image: Winter Mountain Games

Game of Drones: After hours, an unseen army of uphill skiers and snow bikers rules our mountains.

T o the untrained eye, it may look as though Vail’s Winter Mountain Games were a bizarre, one-off circus involving a throng of slightly crazed ultra-athletic types gathering to haul themselves up the mountain in any but the usual way.

But the reality may be even more unexpected. On any given day in winter, long before the ski lifts open for business and again after they close, you will find diehards huffing up Vail and Beaver Creek mountains with skins on their skis, running through the woods on sneaker-stapled snowshoes, and joining phalanxes of friends to test their super-fat bike tires on powder.

“People who weren’t familiar with it were kind of dumbfounded by the size of the tires,” says Darin Binion of the average spectator’s reaction to his snow bike during last year’s inaugural Winter Mountain Games, in which he competed in the on-snow bike criterium and dual slalom. “There are some people who look at the bikes and joke, ‘Where’s your motor?’ It looks big and heavy and slow, but what it can do—especially on snow—is amazing.”

Binion owns the Gear Exchange in Glenwood Springs, a shop specializing in fat bikes, mountain bikes with oversize tires that would be the envy of the Michelin Man and do indeed resemble motorcycles without the engine. He commutes to work on his Hummer-esque two-wheeler year-round; competes in on-snow bike race series in Leadville, Copper Mountain, and Ski Cooper; and meets with friends weekly to ride bikes straight up the mountain on the cat tracks at nearby Sunlight—and then to bomb back down the slopes.

As for those skin-heads uphilling with fur strapped to their skis, a good number of them rank among the fittest mountaineers in the world.

“I’m skinning up the hill an average of three to five times a week,” says Vail’s Mike Kloser, who, as a world mountain bike champion and multiple champion at previous Mountain Games (presented by Eddie Bauer in 2013 and formerly title-sponsored by Teva), is a prime example. “It’s one of those things, like so many people around here, I really enjoy the workout. It’s great to know people are doing it for competition purposes as well.”

When selecting niche sports to be represented in the Mountain Games—both winter and summer, which includes events like “full-contact kayaking”—the first priority for organizers is that each involve a taxing physical endeavor, something that strains the muscles and naturally forces a person’s heart rate up more than gravity-assisted skiing and snowboarding ever could.

“It was really a combination of wanting to build an event that was unique to Vail and keep the spirit and legacy of the summer Games in mind with human-powered sports,” says John Dakin of the Vail Valley Foundation, which conceived of and delivers both iterations of the Mountain Games. “We didn’t want to try to create another Winter X. We took a step back and looked at some of the niche, human-powered activities that people are doing. We wanted something that would give the residents and the guests of the Vail Valley a look into some of these sports that they may never see.”

Even if you miss the Mountain Games, they’re happening all around you, every day of the winter and into summer. You just need to know when, and where, to look. —Shauna Farnell