50 Years of Vail in Words and Pictures

Members of the US Olympic Ski Team (who likely would have competed at Vail had Colorado voters not rejected a bid to host the 1976 Olympic Winter Games) race down the back bowls.

Image: Vail Resorts

Most histories of Vail start with the fateful day on March 19, 1957, when Pete Seibert and Earl Eaton parked Seibert’s army-surplus jeep on the side of US Highway 6 (long before Interstate 70), attached climbing skins to their skis, and slogged up what would become the front side of Vail Mountain. It took them seven hours to climb 3,050 vertical feet to the summit at 11,250 feet, where Seibert first saw what he later described as “the most mind-blowing landscape of all: a series of bowls stretched to the horizon, a virtually treeless universe of boundless powder, open slopes, and open sky.”

Eaton had grown up in a ranching family downvalley in Edwards, later working ski jobs in the winter and prospecting for uranium in the summer. The quiet westerner led Seibert, a boisterous New Englander from Sharon, Massachusetts, to the promised land that day. But the story of Vail can actually be traced back ten years earlier, to when the two World War II veterans first met as ski bums in Aspen and shared their dream of finding and founding the perfect ski area.

Fifty years after first opening on December 15, 1962, Vail in many ways is the gold standard in the ski industry, having shaped major trends in lifts, ski schools, season-pass products, ski-patrol techniques, airline access, ski and snowboard competition, sustainability, and, most recently, social media. Travel to almost any other ski resort in the world, and you’re likely to find someone who, at one point or another, has lived or worked in Vail.

“It’s the center of the skiing universe,” says Susie Tjossem, executive director of the Vail Village–based Colorado Ski & Snowboard Museum and Hall of Fame. “But in its infancy, all those people had lived or worked in Aspen, and Vail stole the brightest, most creative, most innovative risk-takers out of Aspen—the Pete Seiberts, the Earl Eatons, the Morrie Shepards, the Rod Slifers.”

Even the method by which Vail rose from sheep pasture to fledgling ski area in just five years was an innovative funding miracle. Eaton was “The Finder” and early on the force behind the physical on-mountain construction of Vail. Seibert was “The Founder,” the visionary 10th Mountain Division war hero who had studied hotels, hospitality, and ski-area and village planning in Europe and had managed many aspects of the fledgling industry at Aspen and Loveland.

But it was Denver oilman George Caulkins whom many deem “The Funder,” because he borrowed oil-drilling financing techniques and came up with the concept of selling a hundred $10,000 shares that included four lifetime ski passes and the deed to a home-site parcel for another $500. Caulkins and Seibert switched from Pete’s old jeep to a sleek silver Porsche and barnstormed the country, selling shares to, as Seibert later recalled, “friends, relatives, old school chums, country club pals, army buddies, and others.” In that innovative way, they secured a pool of investors with more than just a monetary interest in their dream, and in many ways established the ethos of continual reinvestment that lives to this day.

Another innovator in the early days was Vail’s first marketing and public relations director—a fellow 10th Mountain Division veteran named Bob Parker. He took the competitive spirit of accomplished ski racer Seibert to the next level, inviting race teams to travel to Vail for training, hosting races that led to the modern World Cup, and convincing many in the media that a tiny start-up ski resort far from established ski destinations like Aspen was actually an international racing destination.

Parker also understood branding, coining the moniker “Colorado Ski Country” for Vail—a name later assumed by the lobbying group for the entire state ski industry—and courted national air carriers to service Vail at a time when the Eagle County Regional Airport was a remote and dusty airstrip. Now, many Aspen skiers actually start their vacations by landing in Eagle at a modern airport that in the winter is the second-busiest in the state.

And it was Parker who, along with initial Vail investor Dick Hauserman and original ski-school director Morrie Shepard, lured Austrian ski-racing great Pepi Gramshammer away from Sun Valley, Idaho. In addition to building one of Vail’s first hotels (an authentic gasthof that might have been plucked from his Innsbruck hometown) and one of its foremost ski shops, Gramshammer loaned his name (he’s “Pepi” to nearly everyone) to a steep face on the mountain’s front side and dubbed a Back Bowl run “Forever”—the approximate time it took him to climb out before a lift was installed.

With his expanding local retail and hospitality businesses, Gramshammer served as a perfect talisman for three of Seibert’s original enduring themes for Vail: maintain and celebrate the sport’s European roots; perpetuate the resort’s ski-racing legacy; and invite newcomers to embrace, invest themselves in, and reinvent the dream.

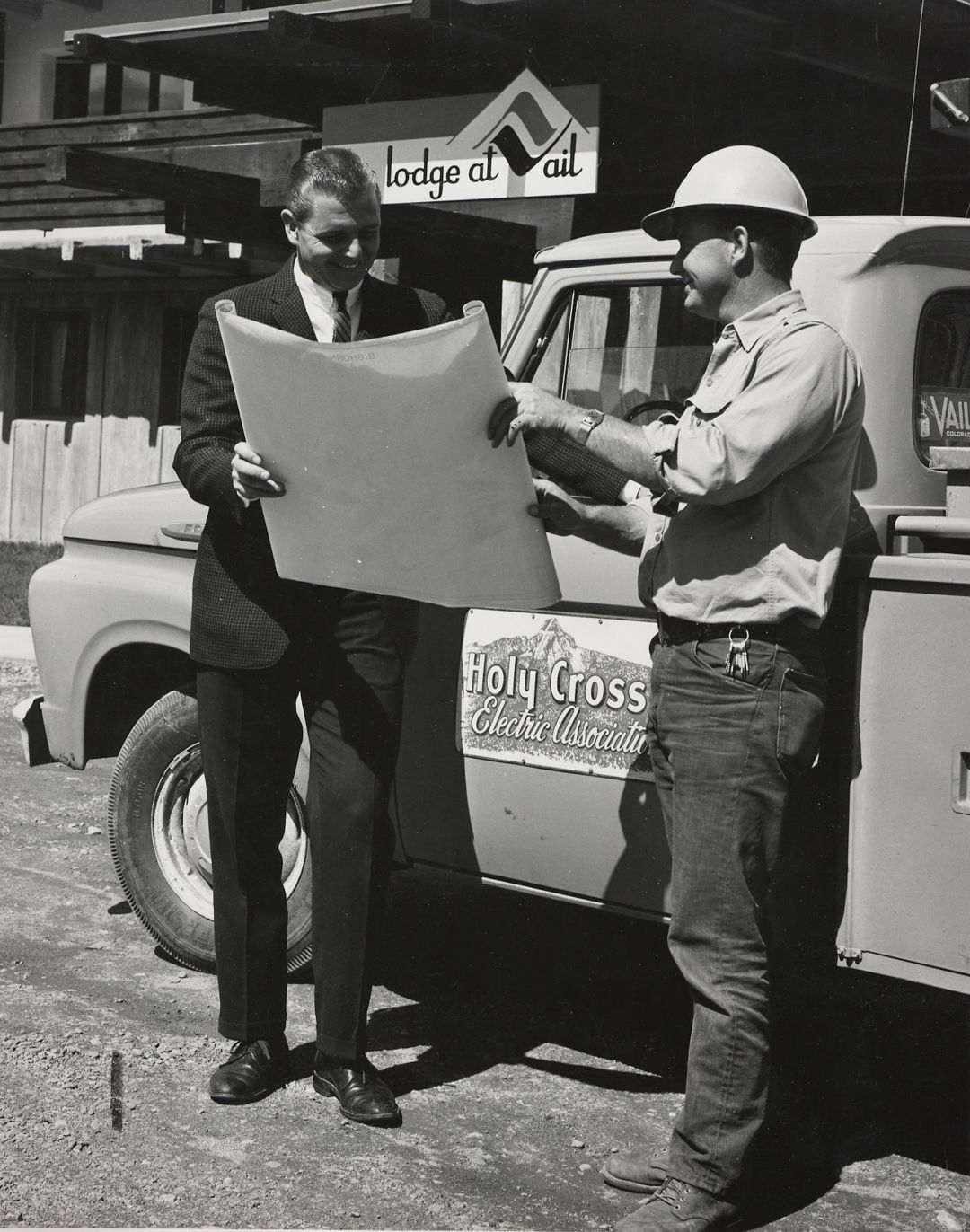

November 1962: The Lodge at Vail opens as Vail’s first hotel.

Image: Vail Resorts

On the Brink

In its earliest days, a groundbreaking ski resort teeters between ruin and success.

Vail in the early 1960s was a frontier outpost, choked in mud and dust and caught up in a gold-rush fever of expectation.

To disguise their intentions from other ski-area speculators, Pete Seibert and Earl Eaton, along with Denver lawyer Bob Fowler and real estate appraiser John Conway, formed the Transmontane Rod and Gun Club. They acquired a 520-acre slice of the Hanson Ranch for $110 an acre in 1958, and in 1960 they bought the 500-acre Katsos Ranch for $75,000.

That privately owned land, at 8,150 feet in elevation, would over time become Vail Village, but the proposed ski slopes that would rise upward to more than 11,000 feet south of town were all on federal land. In the spring of 1959, when the US Forest Service first rejected Seibert’s dream (and permit request) in favor of approving development at Aspen Highlands, the founder appealed to a higher power—friends in Congress—and he won a permit before the end of the year.

One condition of the federal permit required the fledgling company to raise $1.8 million—the price of a modest condo in Vail Village these days—to ensure that the project, on public land, would be adequately funded. To that end, Seibert—with Fowler, George Caulkins, Gerald Hart, Dick Hauserman, Harley Higbie Jr., Fitzhugh Scott, and Jack Tweedy—formed Vail Associates (VA) in December 1959, launching a race to raise cash and build a ski mountain and a village in time for opening day on December 15, 1962.

“As Vail was being built, we were always balancing on the brink of failure, trying to be ready for any surprise disaster that might arrive and never being able to guess how bad the news might be,” Seibert recalls in Vail: Triumph of a Dream.

Many of those disasters were man-made. A forest fire had fortuitously cleared Vail’s iconic Back Bowls in 1879, but in the summer of 1962, before the mountain even opened for skiing, another conflagration—this one sparked by a coal-fired locomotive in Minturn—threatened to take care of all of the front-side trees, too. As the flames raced toward the western edge of Vail Mountain, Rod Slifer, then an assistant ski school director who had moved to Vail from Aspen in May 1962, was picking up the company mail in Minturn because Vail didn’t yet have its own post office. He found a phone, jumped on the local party line, and managed to clear out the gossipmongers who dominated conversation.

“I think it was just saying, ‘There’s a fire! Get off the goddamn line!’” Slifer recalls, noting that he ultimately was able to reach Seibert, who dispatched a work crew to contain the fire at the mountain’s western edge.

With Eaton leading the construction charge, Vail somehow opened on schedule with a gondola out of Vail Village, two chairlifts, and not much snow. But the price was right. Lift rides were free on opening day and later cost $5 ($38.14 today, adjusted for inflation). Still, that first season, livestock grazing nearby pastures outnumbered skiers on Vail Mountain. On one January day, Seibert counted twelve paying customers, and his eight ski instructors often had no one to teach.

Slifer worked for VA ski school for three seasons for $500 a month, plus tips. At the same time, he handled real estate sales for the company and ran a property management firm.

“You couldn’t make a living,” Slifer says of tepid initial sales. “We did have lots for sale—and they were about $5,000 to about $15,000—but the partners had first choice, and they picked all of the really good lots. What was left was a little bit less desirable—so very, very few sales. That’s why I kind of survived on the property management business.”

Slifer later formed Slifer Smith & Frampton Real Estate, a company that now tops $1 billion in annual sales.

Image: Vail Resorts

Trauma and Tragedy

As the resort’s medical industry blossoms, disaster on the mountain ousts its founder.

Dr. Jack Eck first skied at Vail while he was interning at Denver Presbyterian Hospital in the late 1960s, a last hurrah before heading to the jungles of Vietnam, where he served as a flight surgeon and made a promise.

“I said to myself, ‘If I survive this—because it was getting hot up there—I’m going to go to a ski area for a winter,’” recalls Eck, now executive vice president of clinical program development and community outreach at Vail Valley Medical Center (VVMC). “That was my whole thought process.”

After Eck returned from Vietnam in October 1971, Vail’s first doctor, Tom Steinberg, who had come to town in 1965, added him to the resort’s expanding medical staff. For the first three seasons (1962–64) a clinic had been housed in the Red Lion building, but when Dallas Cowboys cofounder and original Vail investor John Murchison broke his ankle while skiing in 1965 and had to be driven by car to Aspen, the Texas oilman donated money toward a bigger and better-equipped medical facility in his Mill Creek Court building. The clinic then was relocated to the site of the current VVMC administrative offices, around which a modern, comprehensive hospital would grow up. This is where Eck landed after Vietnam, anticipating a respite from the horrors of war, only to find himself five years later at the center of one of the worst ski-lift accidents in US history.

Eck says he won’t ever forget that morning in late March 1976, when he was again working as an intern at Denver Presbyterian Hospital and received an urgent call from ski patrol headquarters on Vail Mountain: two filled-to-capacity cars from Gondola 2 had detached from a frayed lift cable and had plummeted 125 feet to the ground; two more cars were in danger of falling; and 176 skiers were stranded, suspended in the sky. He would spend the next few hours on the phone, dispensing medical advice as patrollers tended to a dozen victims, which, despite their best efforts, would include four fatalities.

The accident produced numerous ripple effects, including the sale of Vail Associates to Texas oilman Harry Bass for $13 million in 1976 and the eventual ouster of founder Pete Seibert amid fears of mounting litigation. For Seibert, the gondola tragedy marked the nadir of a decade that had opened with so much promise: in May 1970, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had selected Colorado to host the 1976 Olympic Winter Games. Vail’s founder then purchased land at the base of present-day Beaver Creek that he intended to develop as an Olympic venue, only to have his dream snatched away when Denver voters rebuffed the IOC’s offer in 1972. In February 1976, the Games were held not in Avon, but in Innsbruck, Austria, which had hosted them just a dozen years earlier. Barely a month later, Vail achieved international headlines in the worst way imaginable.

While Vail’s founder exiled himself to Utah, Eck and Vail’s hospital prospered. After two guests suffered fatal heart attacks at Mid-Vail, he set up an on-mountain cardiac program and was instrumental in establishing the hospital’s first intensive care unit in 1980. “Jack’s Place” at the Shaw Regional Cancer Center in Edwards bears his name, and he’s currently helping to spearhead a major expansion of VVMC’s Vail campus. But at age 70, he is slowing down, if only slightly. After forty-one years, this will be Eck’s final season as medical adviser to the Vail ski patrol, although he says he may still carry a radio when he’s skiing on his days off.

“We didn’t have a clue,” Eck says of the humble ski-town clinic that grew into a regional health-care powerhouse. “We just wanted to have a good time ... [I was] just trying to leave Vietnam behind me and all those traumas I had, and just get through life. The community was growing, but we had no idea it was going to be like this.”

The Quad Squad

Buffing a diamond in the rough

The difference between mounting a vintage fixed-grip chairlift and boarding a modern detachable high-speed quad is the difference between being whacked in the calves by a nine iron and settling into a plush sectional sofa. From the beginning of their tenure as owners of Vail Associates in 1985, Rose and George Gillett were all about making Vail one big, cushy couch for skiers from around the world, especially families.

“It was a game changer,” George Gillett says of Vail’s first four high-speed quads, installed for the 1985–86 ski season. Widely credited with launching the arms race that had US resorts rushing to build high-speed lifts, Gillett allows that the four lifts were already in the works when he bought the company from the Bass family for $130 million in August 1985: “They had been ordered, but I don’t think they had been paid for,” he laughs. Today, seventeen of Vail’s thirty-one lifts are detachable quads.

Before their tenure ended in bankruptcy in the early 1990s, the Gilletts (by Vail founder Pete Seibert’s reckoning in Vail: Triumph of a Dream) pumped $65 million in improvements into Vail: adding and upgrading snowmaking equipment, installing still more high-speed quads, and opening China Bowl in December 1988. Although real estate developer Harry Frampton deserves credit for initiating many of these infrastructure upgrades in his time as VA president from 1982 to 1986, for Gillett the goal wasn’t just increasing the mountain’s capacity but improving the overall guest experience, through such steps as expanding parking and public transportation and shrinking lift-ticket and ski-school lines. Modeling that mantra, Gillett himself sometimes worked the phone lines, and at Christmas he even donned a Santa suit and handed out dollar bills to kids.

Fresh from owning and running the Harlem Globetrotters, Gillett and his guest-first focus initially ran counter to the operations-first mentality of company stalwarts like the late mountain manager Bill “Sarge” Brown and ski patrol director and later COO Paul Testwuide. Gillett says his experience in sports entertainment bumped up against the “10th Mountain psyche” that implied guests had to suffer somewhat if they wanted to ski. That attitude changed with the Gilletts and was copied throughout the industry. He knew he—and his business philosophy—finally had been accepted when one day Brown, a former senior sergeant major in the army, gave Gillett a new radio code: “Oh-one.” As in no. 1.

“We came as guests; we didn’t come as owners,” George Gillett says, referring to his family’s ski trips to Vail, which started in 1972, well before they bought the resort. “That’s how we thought about people,” adds Rose Gillett, for whom Rose Bowl at Beaver Creek is named. “That’s how we thought through that process: how can we make your day a little easier here?”

And their legacy endures: last season, Rose Bowl received a new high-speed quad.

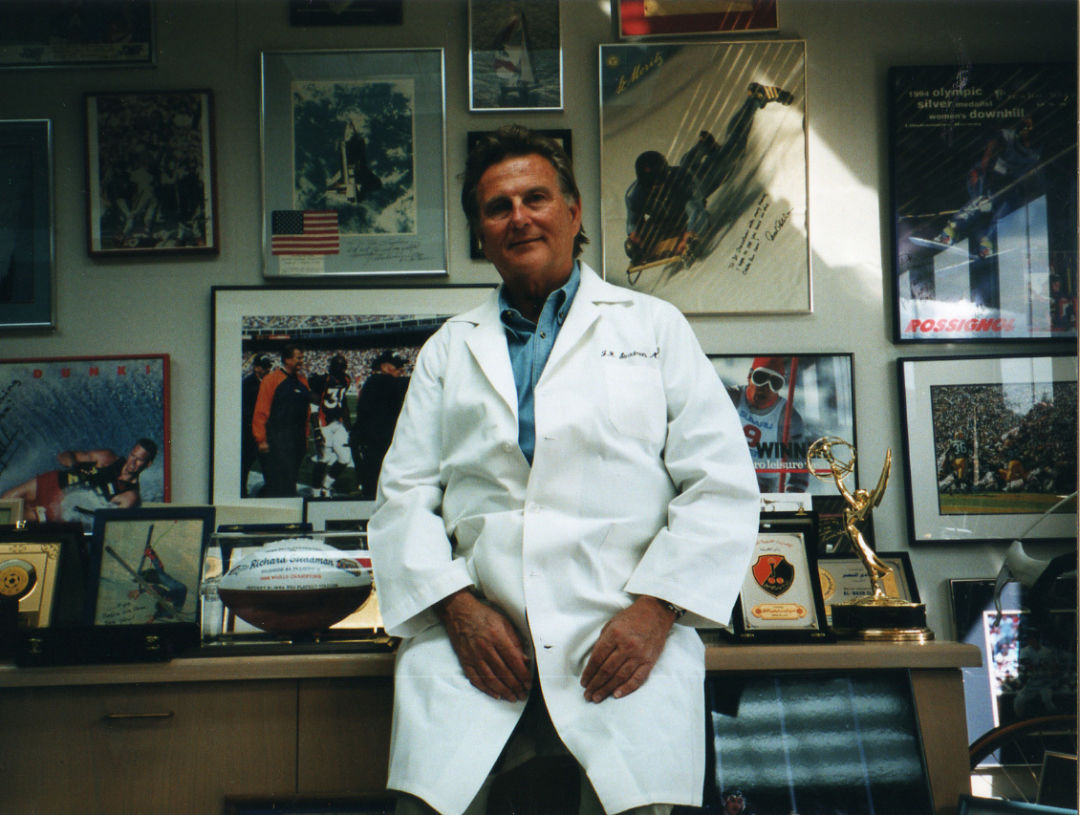

Dr. Richard Steadman, surrounded by mementos from celebrity patients, circa 1990

Image: Vail Valley Medical Center

Vail Reinvested

From Bridge Street to Wall Street

Vail Mayor Andy Daly was president of Vail Resorts in late October 1998 when he told a crowd at a Vail brewery, “Don’t let the bastards get you down!” He could have been talking about any number of misfits and mishaps that bedeviled the company during the turbulent ’90s, but the longtime ski executive was referring to environmental protesters who a week earlier had torched several buildings and chairlifts at Vail to protest the planned Blue Sky Basin ski area expansion.

The rough patch began in early 1990, when charismatic Vail Associates owner George Gillett severely injured his knee while skiing on Vail Mountain with his wife. Noticing his swollen leg at dinner that evening, Olympic skier Cindy Nelson referred Gillett to renowned orthopedic surgeon Richard Steadman, who, as physician for the US Ski Team, was packing for the International Ski Championships in Europe. Not a problem for a resourceful guy like Gillett. After Steadman performed emergency ACL surgery at his Lake Tahoe clinic the next day, the doctor flew with the resort owner in Gillett’s private jet to JFK and offered physical therapy en route, forming a friendship that ultimately led Steadman to relocate his practice to Vail. That bit of kismet cemented Vail’s reputation as an epicenter of sports medicine, launching an era of celebrity medical tourism that continues to this day with the proposed $75 million expansion of Vail Valley Medical Center, overseen by international “starchitect” Michael Graves.

Then, bankruptcy brought on by high-interest borrowing forced Gillett to sell the ski company in 1992 to Apollo Advisors, a New York private equity firm founded by Wall Street financier Leon Black.

In the wake of an October 19, 1998 arson attack, environmental protesters converge on Vail Mountain to try and block construction of Blue Sky Basin. Activists perch in trees, chain themselves to heavy equipment, and cement themselves into overturned cars. Numerous arrests are made, and the expansion proceeds on schedule.

Image: Vail Fire Department

“Everybody was really concerned when Apollo bought it, because [CEO] Adam Aron and Leon Black—they were skiers, but they weren’t real skiers,” says real estate mogul and former Vail Mayor Rod Slifer. “In the past, with Vail Associates, they were all skiers, and then along came Apollo. But they ended up being a good owner; they reinvested like everybody else.”

First the company acquired Arrowhead, a small private ski area west of Beaver Creek that Vail founder Pete Seibert helped develop in the 1980s, and connected it to Bachelor Gulch and Beaver Creek. Apollo also pursued, and won, a bid for an unprecedented second World Alpine Ski Championships, which returned to the valley in 1999. Then in 1996, the company installed a new, high-tech gondola connecting Lionshead with the mountaintop Adventure Ridge area, offering nonskiing visitors access to a slew of year-round activities, including laser tag, tubing, ice skating, snow biking, and nighttime dining. And despite the opposition from environmentalists, Apollo plowed ahead with Blue Sky Basin.

In 1997, Vail Associates, renamed Vail Resorts, went public while simultaneously acquiring the nearby Breckenridge and Keystone ski areas via a merger with Ralston (yes, the cereal and pet food company). The conglomerate then began systematically acquiring lodging properties—including Vail’s first hotel, the Lodge at Vail—as well as retail outlets and restaurants in a series of moves that made local independent business owners decidedly nervous.

But the spark to the powder keg was the looming construction of Blue Sky Basin, where environmentalists feared the new bowls (known today as Pete’s and Earl’s)would destroy endangered Canada lynx habitat. After a summer of protests on Vail Mountain, a small band of environmental activists started a series of fires on October 19, 1998, that caused an unprecedented $12 million in damages.

All the lifts were repaired, and a temporary replacement for the torched Two Elk Lodge was up and running for the 1998–99 ski season. As for those “bastards,” the three Earth Liberation Front members responsible for the arson were apprehended, convicted, and jailed.

“I got admonished for my statement because there were kids in the audience, but at the same time it was something that people took away and remembered,” Daly says. “It was sort of a rallying cry for the community. We were obviously able to overcome the adversity and went on to a terrific 1999 World Championships.”

Image: Vail Resorts

New Dawn

With the founders’ dream realized, Vail defies a downturn with a next-generation face-lift.

After weeks of buildup, including a benefit concert by Roger Daltrey at Dobson Ice Arena, the new millennium at Vail officially began with a ribbon cutting on Jan. 6, 2000, a classically crisp, cold Colorado winter day along the frozen banks of Two Elk Creek at Blue Sky Basin. Among the host of dignitaries assembled that morning, the most notable guests of honor were the resort’s founder, Pete Seibert, and its finder, Earl Eaton.

The new Pete’s and Earl’s Bowls, north-facing gladed runs south of Vail’s existing Back Bowls, added an area larger than all of Aspen Mountain to an already enormous complex of ski terrain. And with the dedication, the tumult and terror of the previous decade’s environmental protests and ecoterrorism attacks receded into the past like a fading nightmare.

Named for the Ute Indians who inhabited the Vail Valley in the 1800s—the “Blue Sky People”—the new terrain dramatically changed how visitors skied the mountain, alleviating crowds in the existing Back Bowls and providing a north-facing, 650-acre stash of fresh snow far from Vail Village. Although lifts and facilities would continue to be upgraded on Vail Mountain throughout the 2000s, the big ski-area projects were done, and the focus turned to revitalizing the town itself.

Starting with the renovation of the Vail Marriott Mountain Resort & Spa in 2002, Vail saw a billion-dollar wave of redevelopment that included Arrabelle at Vail Square and a new skier bridge in Lionshead; Solaris at Vail, the Ritz-Carlton Residences, the Four Seasons, and the Sebastian in Vail Village; and a complete makeover of Vail’s “front door,” where the Lodge at Vail meets the ski hill at the old Vista Bahn Express chairlift.

It was a breathtaking decade of reinventing a town that had been somewhat hastily conceived and constructed in the boom days of the ’60s and ’70s; at one point town officials joked that the construction crane was the official bird of Vail Village. The process was slowed only slightly by the post-9/11 economic dip, and, incredibly, even the near-apocalyptic recession of 2008–09 couldn’t derail what locals came to regard as Vail’s New Dawn.

In mid-decade, Vail Resorts’ chief executive Adam Aron (now co-owner and CEO of the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers) passed the baton to longtime Apollo Management executive Rob Katz. Although Katz was a fresh-faced 39 when he took over as CEO in March 2006, he had served on the Vail Resorts board since 1996 and was working for Apollo when it took control of Vail from George Gillett in 1992.

“I had an understanding of the ski industry, and the history of the company, and the people within the company,” Katz says. “That really gave me an amazing head start to make decisions that were colored and helped by that experience, even though for many it seemed like I parachuted in.”

Katz immediately rankled locals by moving the company headquarters from Avon, at the base of Beaver Creek, to Broomfield, a suburb north of Denver. But as Katz sees it, the move to Broomfield better positioned the company as it expanded its holdings nationally, acquiring three ski areas near Lake Tahoe (Kirkwood, Northstar, and Heavenly), summer resorts in Wyoming, and hotels and lodging management contracts from Washington state to the Caribbean. The CEO also ruffled feathers when he launched the deeply discounted Epic Pass, which locals feared would encourage overcrowding as Front Range skiers inundated resorts in Eagle and Summit Counties—a move many analysts have since credited with keeping the company afloat, and ahead of its hard-hit competitors, during the recession.

Like his predecessors throughout the years, Katz continues to pump money back into the company, investing heavily in on-mountain social media, signing big-name winter sports stars like Lindsey Vonn and Shaun White to marketing deals, and luring the 2013 US Open Snowboarding Championships and the 2015 World Alpine Ski Championships, continuing the emphasis on big-name events championed by Pete Seibert. It’s a strategy that honors the resort’s past, and perhaps more important, as Katz puts it, aims to secure its future by “connecting to the next generation of skiers.”

By Road or Rail

It won’t take the Olympics or maglev trains to lure more skiers to Vail.

Fast-forward to Vail’s centennial in 2062. Looking into their crystal snow globes, experts see three major factors limiting the amount of change Vail will undergo over the next half century: lack of land, lack of access, and resistance to ski-area growth.

“I always compare Vail and Beaver Creek to an island,” real estate guru Rod Slifer says. “Islands are surrounded by water, and we’re surrounded by national forest, so we’re really limited in terms of growth. The key land has been developed.” He points to redevelopment such as Vail Resorts’ proposed billion-dollar Ever Vail project (with a new gondola, hotel, condos, and shops west of Lionshead) as the only real opportunities for expansion once the real estate market rebounds.

Slifer also notes that about half of visitor dollars spent in the valley derive from Colorado’s Front Range. The ever worsening congestion on Interstate 70, he suggests, could discourage Front Range skiers from making the trip—already a four-hour return on most Sunday evenings—thereby limiting Vail’s business growth in the coming years.

With few federal and state dollars available to add more lanes to the highway (not to mention local opposition), former Vail Resorts President Andy Daly says the only viable long-term solution along I-70 between Denver and Vail may be high-speed rail. But, he adds, the only way such a system is likely to be built is if Colorado finally fulfills Peter Seibert’s ultimate dream and lands the Olympic Winter Games. (He points to the federal infrastructure dollars that flowed to Salt Lake City in 2002.) However, the earliest Colorado could hope to host the Winter Games is now 2026, and even that date could be delayed if the United States Olympic Committee decides to pursue the 2024 Summer Olympics instead.

Seibert modeled his dream ski area on the great European resorts, many of which are connected by state-funded rail. But experts point to Europe’s much greater population density and the proximity of its ski areas to large cities—and a greater public willingness to pay much higher gasoline taxes to fund mass transit. A 2010 Rocky Mountain Rail Authority study put the price of conventional high-speed rail between Denver International Airport and the Eagle County Regional Airport at $16 billion; federal money to fund high-speed rail, if it ever becomes available, would probably be earmarked for major metro areas along either coast, according to most rail observers.

Nevertheless, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) is seriously studying rail along the I-70 corridor to solve congestion during peak travel times. CDOT requested proposals from mass transit companies in August and received more than 150 responses, including one very futuristic—and critics say far-fetched—pitch from Texas entrepreneur Robert Pulliam, who is proposing a trackless, elevated transit system (pictured at left) resembling a dental flosser that he says would be more economical to build and better suited to deal with the steep grades and adverse weather of the Rocky Mountains than traditional rail designs.

Regardless of whether Vail ever lands the Olympic Winter Games or is linked to Denver by rail, Ford Frick, managing director of BBC Research and Consulting, a Denver-based economic research and planning consulting firm, predicts that Vail will continue to lure ever more visitors, from near and far, into the valley over the next fifty years.

“The resorts have a lot of difficulty in evolving now because they’re kind of built out ... and there’s great institutional resistance to change and growth,” says Frick, who specializes in real estate, resorts, and tourism practices for BBC. “But the Rocky Mountains will continue to have an appeal. There is something about mountains that we are genetically predisposed to respond to. These are unusual and emotional and extraordinary places, and so people will want to be here—and there will still be lore and romance.”

And history.