Resort and Town Confront the Fallout of a Terrible Year

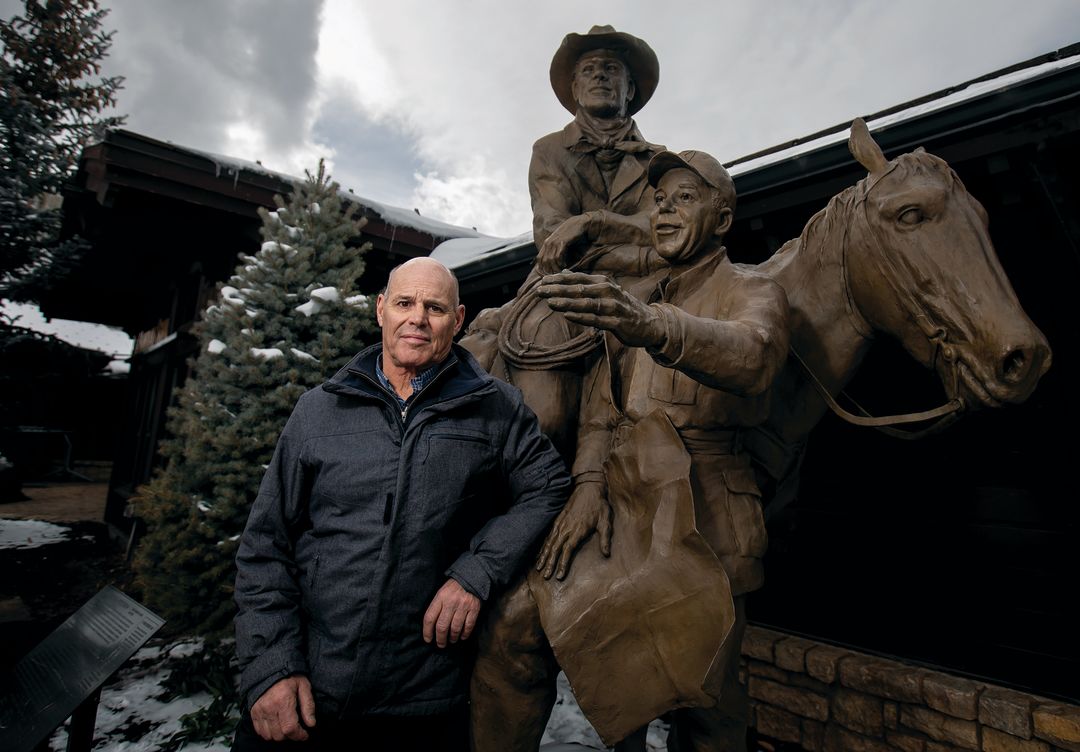

Vail Town Councilmember Pete Seibert Jr. with a statue of his father, Vail co-founder Pete Seibert, in Vail Village.

Image: Dominique Taylor

Ever since Vail became a world-class destination in the 1960s, the ski resort and the town have been inextricably linked—not just by their shared name, but also by their successes and failures. The relationship between the two entities has ebbed and flowed through the decades, but this past winter marked a tipping point in the eyes of many locals.

Due to a perfect, pandemic-driven storm of circumstances—discounted Epic Pass prices that led to record sales (nearly 80 percent more than two years prior), a global labor shortage, a worsening valleywide housing crisis, and visitation surges that overwhelmed the local infrastructure and created exceptional lift lines—Vail Resorts found itself in a public-relations pickle halfway through the season. A fusillade of negative stories in national news outlets ranging from the Wall Street Journal to Outside magazine questioned the company’s business strategy and ability to serve the masses it was courting. The corporation’s once-bulletproof stock price plummeted.

Locally, however, the concerns were more acute. With all of those new Epic Pass holders (skier visits were up by 12.5 percent last season across all VR resorts), the town’s public parking structures filled to capacity 53 times, more than triple the tally of a normal winter, forcing overflow vehicles onto the shoulder of Frontage Road. Vail Resorts’ operational challenges here and elsewhere, particularly at Stevens Pass in Washington (where long lift lines, limited parking, and packed terrain prompted 39,000 skiers to sign a petition complaining that “Vail Resorts has contributed more to the destruction of our ski communities and our sport than they have created value”), triggered big-picture conversations about Vail’s brand and potential long-term implications if such challenges were to persist in future seasons.

At the Town of Vail’s annual retreat in February, several councilmembers voiced their frustration in startling terms—and expressed an urgency to collaborate with Vail Resorts’ higher-ups on decisions that affect more than just the ski resort. “They’re not respecting where we live,” said two-term councilmember Jen Mason, the executive director of the Colorado Snowsports Museum and Hall of Fame.

The company’s PR crisis had subsided by April as Vail Mountain neared the end of its season, but the community’s long-term concerns had not. “This is serious, and it has huge implications for our future,” says Vail Mayor Kim Langmaid, who grew up in the valley and says she heard widespread worry from locals this winter. “The Vail brand and community that people have worked so hard to create over the last 60 years, it means a lot to everybody here that we continue to do a good job moving forward.”

Councilmember Pete Seibert Jr., whose father cofounded the ski resort, expressed similar sentiments. “When they reduced the price and sold 2.1 million Epic Passes, we became vulnerable to having all systems overloaded,” says Seibert, who works as a real estate agent in town. “And that’s just not where we want to be.”

Vail Resorts addressed some of its problems in March, increasing minimum staff compensation to $20 an hour (a nearly 30 percent bump) and offering corporate employees who had been required to work on the Front Range the option of returning to the valley. Kirsten Lynch, who took over last year as CEO, admitted in an open letter to employees on March 14 that the company had “fallen short” as an employer.

Langmaid met with Lynch for the first time in early April; she and Seibert remain hopeful that the company will be more open to town input following this winter’s problems. Vail and Beaver Creek senior communications manager John Plack says the company “continues to partner deeply” with the town and the community. “We engage with town staff and elected officials in numerous forums and prioritize those relationships,” he says, “We believe we have a shared vision for the sustainability of the local environment and for the long-term environmental and economic success of our community.”

Seibert hopes Vail Resorts will shift from quantitative to qualitative analysis when making future decisions. “We’ve got to shake ’em up a little and get their attention,” he says, “but then we have to be productive.”

Adds Langmaid: “I feel like Vail Resorts understands the importance of the Vail brand and legacy, and moving forward I really hope they understand the sense of urgency that the community feels, because perception is reality for many people. No matter what the data says, there is an experiential aspect and perception to all of this that needs to be addressed. We have to work together in a more holistic fashion to look at the big picture.”

Grousing Over Housing

The relationship between the resort and the town also is being tested by a controversial employee housing project in East Vail that has been in the works for years. Vail Resorts announced in April that it intended to start construction this summer on the 61-unit Booth Heights complex, which could house 165 resort workers.

But contention remains over the parcel on which the company proposed to build—23 acres that for generations has served as periodic habitat for more than 90 bighorn sheep that, employee housing proponents note, have been crowded onto the tract after decades of unfettered vacation home development in the area. Vail Resorts argues the town already approved its plan; construction was simply delayed by the pandemic. The town would like to partner with VR to develop land it owns in West Vail that’s within walking distance of both ski villages. At press time in early May, at a packed proceeding, the council voted 4-3 to condemn the East Vail parcel, a first step in wresting it from VR and a stunning rebuke of the county’s largest employer and its attempt to invest $17 million in workforce housing.

The debate is unfolding, of course, against an ominous backdrop: never in Vail’s history has there been a greater need for affordable places for local workers to live. “There is NIMBYism going on [from homeowners opposed to the Booth Heights project] but I don’t think it’s the best site for that type of housing,” says councilmember Pete Seibert Jr., who voted against condemnation. “We don’t want to take some kid from Argentina who comes to Vail for a season as a lift operator and park them out in East Vail.”