How Not to Become a Statistic on Holy Cross

Matthew Smith poses for a snapshot in the Bowl of Tears before a near-disastrous 2016 summit ascent up the Cross Couloir.

Image: Courtesy Matthew Smith

Lost Boys

When Matthew Smith and Tommy Hendricks reached the bottom of the Cross Couloir in late November 2016, the Colorado Springs teenagers geared up for what they expected to be a two-hour ascent to Holy Cross’s summit and a quick jaunt back to their tent in East Cross Creek. The duo had partnered on some of the toughest fourteeners in the state, including Capitol and North Maroon peaks near Aspen. Yet none captivated them like Holy Cross. “All the other mountains I had climbed didn’t have that draw,” Smith says. “It just seemed like it would be really rewarding to get up that.”

Seven hours after they started up the couloir, having been slowed by sugary snow and a raging autumn blizzard, Smith and Hendricks summited and looked for the trail down. They couldn’t find it. Not knowing which way to go, they hunkered down at 13,800 feet with 50 mph winds stinging their cheeks and spent a harrowing night shivering together in the elements.

The next morning, the teens, best friends who met through Coronado High School’s rock climbing club, tried to find their way down. But they rappelled into the wrong drainage and got trapped, eventually spending a second night exposed to subfreezing temperatures. Smith made a bed of pine branches that they spooned on top of to keep warm. He wished he’d brought his waterproof matches and thermal bivvy, both of which he left at home to save weight.

After a second night out, the boys grew desperate. Scott Sutton, a volunteer member of Vail Mountain Rescue Group who was coordinating the rescue mission, had already sent two teams into the field. They’d found no sign of Smith and Hendricks. An aerial search had come up empty, as well. Then, just before Sutton called off the search and essentially presumed the boys to be dead, a rescuer on the mountain spotted “anomalies in the snow that didn’t look like animal tracks,” Sutton recalls. An orbiting aerial reconnaissance plane spotted the tracks and vectored an Army National Guard Blackhawk helicopter to the boys, who were long-lined out of the wild and to safety. “They were literally 15 minutes from death, because I was pulling everybody out,” Sutton says.

Smith and Hendricks, who suffered hypothermia and frostbite but made full recoveries, didn’t need to be told how lucky they were. Now, they stress the need for humility and over-preparation on Holy Cross and other challenging peaks. “We didn’t take it as serious as we needed to,” Smith says, “in part because we’d done a lot of hardcore rock climbing, and a lot of the mountaineering we’d done was pretty easy in comparison. But after that experience I switched my goal from a trip up the mountain to an attempt, and to be safe and efficient.”

Without a Trace

Not every rescue ends happily, or with any clarity at all. Such was the case of Michelle Vanek, a 35-year-old mother of four from Lakewood who disappeared while hiking the Halo Route to the summit in September 2005. Vanek was with a friend, Eric Sawyer, on the trail approaching the summit, when she became too tired to commit to the final push to the top, Sawyer said later. Before continuing up the trail, he told her to traverse around the west face and meet him on the North Ridge after he summited. She was never seen again.

Hundreds of searchers, aided by five helicopters, spent more than a week looking for Vanek. Theories abound as to what happened, ranging from foul play to her falling off a cliff and into a rock crevasse. A vicious thunderstorm blew through the area around the time Sawyer said Vanek went missing. Dogs couldn’t pick up her scent. “We’ve never found anything from her,” says Sutton, a 25-year VMRG veteran. “Not so much as a piece of clothing or food wrapper—nothing.”

Still, every summer VMRG members keep looking on their own when they hike the mountain, adding to the areas that have already been searched. And so the search continues, until perhaps one day, the mystery will be solved.

The Curious Case of Captain Button

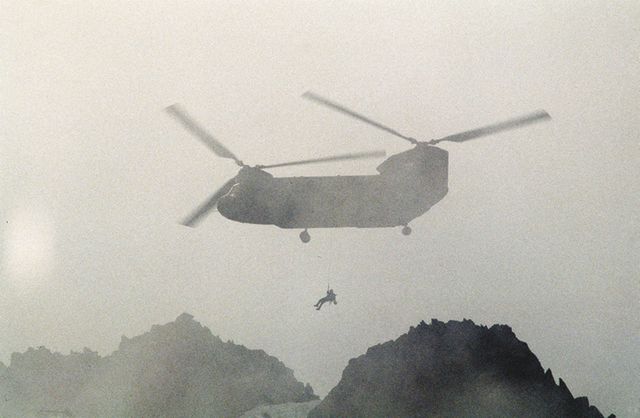

An Army National Guard CH-47 lowers a recovery team member onto Gold Dust Peak in 1997 to search the wreckage of a crashed military jet.

Another unsolved mystery in the Holy Cross Wilderness began seven years before Michelle Vanek took her ill-fated hike, when Air Force Captain Craig Button smashed his A-10 Thunderbolt jet into the northwest face of 13,365-foot Gold Dust Peak on April 2, 1997. Button had taken off that morning from Tucson, Arizona, as part of a training mission, then broke formation and disappeared. Searchers found the remains of his plane 18 days later, in an area as remote as it gets in the Holy Cross Wilderness. It took much of the summer to remove the wreckage by helicopter, piece by piece.

Nobody knows why Button left his wingmates, or whether the crash 800 miles north of his base was intentional. Nor do we know what happened to the four, 500-pound bombs he was carrying. No trace of them was found, though witnesses reported hearing loud explosions in northern Arizona and near Aspen and Telluride that day.

6 Safety Tips

Start early. You’re exposed above tree line for longer on Holy Cross than on other peaks, which means fast-developing afternoon thunderstorms pose a greater threat. Plan to be off the peak by 11, which for most hikers means leaving the trailhead before sunrise.

Stay on trail. For decades, the Vail Mountain Rescue Group conducted an alarming percentage of its summertime missions on Holy Cross, many for wayward hikers who descended west, instead of north, following the fall line from the summit. But since a pair of trail angels installed a sign at the summit two summers ago (with a north-pointing arrow directing descending hikers back to the unmarked ridgeline trail), Holy Cross rescues have been rare.

Plan for the worst. Pack for the dire scenarios you hope not to encounter, and the worst alpine weather conditions. Essentials include thermal and waterproof layers, a warm hat and gloves, sunglasses, sunscreen, extra food and water, and a headlamp with extra batteries (since you may be hiking back in the dark), as well as a cell phone with a backup battery. Since cellular service can be unreliable even at the summit, wise hikers carry a satellite-enabled text messaging device or personal locator beacon (such as a SPOT or InReach device) in case of an emergency. “You can rent one from REI if you need to,” says longtime VMRG mission coordinator Scott Sutton. “Think about the what-ifs.”

Stick to a plan. Problems often arise when people break from a predetermined plan. If you decide to hike a different trail, tell someone, or leave a note on the dash of your car with your starting time and date, phone number, and intended route. Because if something goes wrong, rescuers have a much greater chance of finding and helping you if they know which way you went. Also, if you get lost, stay put (see “Plan for the Worst” left). Moving targets are harder to find.

Do your research. Ideally, go with someone who knows the route you plan to take. If that’s not possible, stop at the local US Forest Service ranger station at Dowd Junction north of Minturn, pick up a Recreation Quicksheet for the hike (or download one at fs.usda.gov/whiteriver) and ask as many questions as you can. Knowing where you’re going and what to expect plays a huge role in the outcome.

When the worst happens, call 911. If you have an emergency on the mountain and truly need help, don’t hesitate to call or text 911 (even if your phone won’t dial out, text messages often will send) and a dispatcher in Vail will alert Vail Mountain Rescue Group, which never charges for a rescue. But be prepared to wait: due to the remoteness of Holy Cross, it may take hours for your guardian angels to arrive.